Some thoughts on an outline of the current covid-crisis and thinking infrastructurally.

If anything this text is about getting thoughts in order in the midst of the fear and the isolation and the unknown. To say this crisis is a perfect example of the power and the weakness of current infrastructural analysis is not to disassociate from the deep sadness that unfurls in the presence of the covid-crisis. Rather, it is to reflect on how the human impact is ongoingly pulled through infrastructure and how this makes calls for change difficult to address. Putting a stop to much of the texture, rhythm and necessity of the everyday — in all but the most essential sense — the crisis reveals in dramatic terms the lay of the land, the inequalities and the key work and workers that make up and maintain that everyday. These are inequalities totally connected to how the maintenance and valuing of the basic conditions of social life of distributed, differentiated and politicised. It also shows the limits of reacting practices to change infrastructure once the interruption of mass-infection and resulting suspension of social and economic activity — not for want of trying.

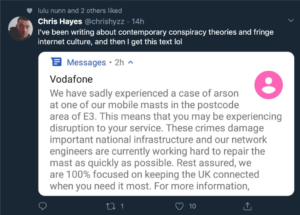

Where we can define infrastructure as that which suspends and maintains the forms and modes of transition, transmission and reproduction that make up a sense of normality, the scale and scope of what the covid-crisis shows about daily life is as unprecedented as it is disruptive. As such it is met by calls for both a need for normality (not lockdown, reduced health threat) and presents the kind of revolutionary conditions that make calls for the vast changes to what normality might look like both possible and politically necessary and palatable. Why for instance would many workers want to go back to the conditions before? Why return to destructive economic and industrial processes. And at the same time the infrastructural dimensions of this crisis show how infrastructures are susceptible to mundane as well as wildly-opportunistic narratives that seek to normalise, make sense of and exceptionalism its local quirks and desires – evangelicals, fascist conspiracy, charity and battles ‘waged’ and ‘lost.’ The overlaying of these narratives with the material realities, shifts and breakages highlights a problem in how we attach the content of narratives that make infrastructure reliable and ‘everyday’ to the conditions we experience, and how these narratives actually serve to construct infrastructure.

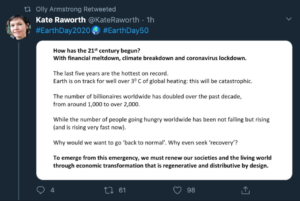

(Tweet by Kate Rayworth on #Earthday2020, 9:54 AM · 22 April 2020 (link). Raworth is the author of Donut Economics)

The art world in particular stands as a good example of these calls. It is precarious, with little ability to react to economic fallout and is already laying of both workers and future programming and funding.[1] Yet maintaining a conceptual and performative autonomy form the medical, numerical, scientific and economic imagination of the pandemic and the metrics tracking it, the art field is also full of big ideas and big claims about a crisis from which it is at the same time distanced from.[2] These claims include those which already reimagine the world anew,[3] but whose conditions of possibility – radical social upheaval — were previously only speculative and mythical in a constantly-out-of-reach horizons of possibility;[4] yet now with new deal-style propositions it is possible to at least realistically imagine “entire school districts employed artists to give Photoshop tutorials for hundreds of students via Zoom,” and “large-scale public or environmental art projects sweep[ing] the land in an age of social distancing and climate urgency.”[5]

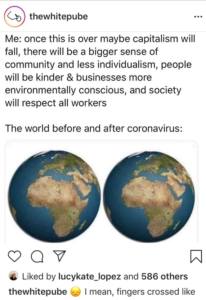

(Instagram post by thewhitepube, 22 April 2020 (link))

However, while everyone claps and makes rainbows for key workers — once little cared for or venerated: from NHS and social care staff, to teachers and bin-collectors, to delivery drivers and supermarket staff — in an emotional reaction as much as one spurred on by the shock of the confrontation with the possible loss and just about maintenance of the basic infrastructures we rely on (from food, healthcare and waste disposal), talk of the possibility of change is hampered the lack of critical and discursive vocabulary through which to rebuild the difficult to discuss unfolding, relational, trans-dimensional and trans-positional conditions of what is called normality. We won’t go back to what was normal before in any whole sense, but the ‘return’ will be very much defined by ideas of preserving what — as all infrastructure is relied upon to do — must be continuous with what we have learned to expect before the crisis, and with what we can anticipate in the future. Infrastructure is seen as the answer, even if it only appears like one: central banks step in to preserve core aspects of everyday — oil and finance and credit — with social support implicitly tied to payback that currently see little chance of being for the top. Or, bottom-up mutual aid replaces infrastructural life support in ad hoc and totally functional ways. The fact that infrastructure must repeat in order to be infrastructure shapes the temporality of any calls for change, and as such this repetition determine how any change might be actually possible and therefore realisable.

Infrastructure is in this way difficult to really change since we rely on it for a semblance of normality and sustainability; we depend on our expectation of it. In art this dependency is seen in the negative space left by funding that looks increasingly uncertain, institutional revenue is nose-diving, freelance fees and income has evaporated, and art schools and universities face an immediate existential crisis that is coupled with likely questions of social utility of arts and humanities courses in the incredibly hard times ahead. This is notwithstanding the pragmatic infrastructural-survival mode that has seen numerous support groups, covid-resource pages and solidarity syndicates[6] that spring up at the grass roots level, where precariousness is endemic. Nor packages such as in Germany, where €50 billion is promised to support the country’s cultural workers and industries, in part to maintain cultural and social solidarity – at the German and more tellingly at the EU level.[7]

Nonetheless defined by the institutional consequence — whether its specific instances, or in the loss of the value art is said to provide — these responses appear to remain trapped within the disciplinary boundaries and autonomy that set how art operates as an inwardly-defined and -constituted sector. At the heart of many of the responses see art as a space apart from the rest of the world in which to rethink what normality we might return to. But, this cuts off the response from the calls to remodel the normality that they seek to hold onto some semblance of.

This tension is of course caught in the need for maintaining basic material conditions for those affected, but meeting this implicit necessity through a continuation of the infrastructural conditions from before, can also be seen to shortcut to the possibility of changing that before. And outside of those already embedded functions, the images of how we might depend on infrastructure — in an ideal, pragmatic, or indeed catastrophic sense — can often, as Lauren Berlant describes, only every be drawn through propositional ontologies for which the world must “create infrastructures to catch up” with them (2016, 395). Here the dominance and limitation so the institutional approach to this problem – representation / symbolic / maintaining autonomy and notions of cultural value and articulation and organisation can be seen in pre-existing visibility-based support from Arts Council England (any recipients must have been already public funded; and must compete within a vastly insufficient pool of 8000 grants), fragmentary foundations and philanthropy in the US, the rush to online exhibitions, and the wild rush to fill time with endless reading lists and video playlists (speaking to both the imposition to appear busy and to stay ‘relevant’). The question is how the aftermath and therefore the present that sustains and leads us there might be constructed as a different kind of normal.

(Tweet by Chris Hayes, @chrishyzz, 8:14 PM · 22 April 2020 (link))

Quite different dynamics are at play ‘outside’ of the disciplinary boundaries of art. At one level this can be seen in the interdependence and interoperability of oil and finance markets— where, as the crisis began to collapse demand for oil, the US federal reserve had to step in to save a deeply entangled US economy and finance industry: otherwise the whole world economy could’ve been at stake. (See: Tooze, Thompson and Runciman, April, 2020, available at: https://www.talkingpoliticspodcast.com/blog/2020/227-adam-tooze-on-the-crisis/.)

At another level, an awareness of the politics and possible stakes of infrastructure are much clearer when framed around what cultural critique Egbert Alejandro Martina has described as the conditions of infrastructural liveability — a metric that has long been implicit to knowing and experiencing what he calls “black urban space.”[8] Here, we can look to calls and potential experiments in Universal Basic Income as in Spain for instance.[9] Such particular infrastructural imagination might be culturally and historically-specific, but they also highlight the need to understand the changes that might be possible not just in the symbolic — institutional sense — but in the unfolding, mundane and deeply entangled and complicit sense of infrastructure, of support, resources, repetition and reproduction and the figures it shapes. For instance, one of the things that Covid-19 has shown of infrastructural operations is how fragile the parameters of the figure of the infrastructural user can be. With the removal of contact and users because of a viral particle so small 600 of which could fit across the human hair, has radically disrupted most user-parameters and revealed the different risks afforded to and thus inherent within other infrastructural figures – in particular those whose bodies, labour, lives are part of infrastructural provision: from delivery to care staff, supermarket workers to distribution centre workers. The radical disruption that might come from an interruption of the habitualised patterns, distributions and boundaries of care and reproductive labour is an argument familiar to the campaign for wages for housework of post-marxist feminists such as Silvia Federici; as is the case that it is possible to map out these relatiosn and operations in advance of the collapse a demand for wages for reproductive labour would precipitate. In the case of the covid-crisis, that is to say we could see these relations before the current crisis made ignoring them less possible. If we can consider infrastructure as reproductive as much as productive this critical legacy might be a useful place as any to think about not just who is at the core of any critical new normality, but how and what they do is rethought, and how that might be part of restructuring what we rely on for it. Ultimately, that is to say in how we might remake the sustainability and suspension of certain imaginaries and values in relation to material, reparative, and useable infrastructural conditions of access and anticipation of use and needs-met that manifest them.

What these examples show, where systemic or living reproduction is in different ways already on the surface is an imaginary for rethinking infrastructure as a socially relevant field. Already there at the technical and formal, aesthetic, ethical or symbolic level it does not need to be ‘revealed’ through a moment of crisis, this sense of infrastructure is both changeable and critiqueable, analysable and implicitly known — the means of responding to the crisis is already to hand (the effects of that crisis notwithstanding).

How quickly we seek, create, and attune to a version of normality, even defined by crisis. Infrastructures is so deeply linked to structures of anticipation and expectation that it is notable how little it is described and critiqued within our understandings of the social world. While we want to get back to normal now — perhaps this is more a question of limited individual freedoms more than a lack of capacity to normalise those limits. As such, normality as a guide to the replicability and commonality of infrastructure might also point to the need for new institutions and institutional relationships to infrastructure through which to make, unmake and institute normality, to make it changeable. This might be an institution in the loosest sense that is immanent to infrastructure and the variability of the unfolding relations that make it up.

Whether art in its current institutional forms be able to affect any change on that normality, or perhaps even if it will survive this crisis, will depend on whether it can see itself in such infrastructurally-relevant terms. This survival could mean more speculative relations to infrastructural conditions to those drawn in reaction to the disruption to the normality of the art world; or imply those only imagining a new world based on the institutional parameters of art from that normal. Could for instance the interdependence of art to other industries as be used as a bargaining chip in the funding of art — a strategic non-autonomy as with oil and finance, or as was leveraged in the case of the German bail out.

Where talking about the infrastructural takes us into the domain of liveability and the very sustainability of the reproduction of life, the autonomy of art can no longer be as the basis for a critical remaking of getting back to ‘normality.’ Instead, at the centre of this task, it seems like the very question for the art field — or whatever comes of/from it — is to re-establish the terms and relations of its interoperation and interdependence. Furthermore, to redistribute the agency that defines the limits and parameters of the dynamic relations that constitute infrastructure. Something perhaps akin to the before and before discussed by Harney and Moten: an undercommons as the infrastructure to come.

notes

[1] https://frieze.com/article/whole-generation-artists-might-be-wiped-out-carolyn-christov-bakargiev-museums-care-and;

[2] https://frieze.com/article/why-covid-19-might-be-our-chance-reimagine-arts;

[3] https://www.artforum.com/slant/hannah-black-and-philippe-van-parijs-discuss-universal-basic-income-82760

[4] Claims whose critical vectors are nonetheless complicated by current events. With contemporary art for instance, its creation of difference within and against the fantasy worlding of convergence and standardisation by post war globalisation has in fact been shown by this crisis (among others) to now be the very mode through which state and corporate power is expressed in a multipolar and ever-more nationalist / nationally-defined world and crisis. (See Tooze, “Shockwave,” in London Review of Books (4 Apr 2020), available at: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n08/adam-tooze/shockwave)

[5] https://frieze.com/article/can-germanys-cultural-bailout-set-groundwork-21st-century-new-deal

[6] Just a range here: https://www.are.na/tom-clark/covid-resources-c98jrh1a7c0

[7] https://frieze.com/article/can-germanys-cultural-bailout-set-groundwork-21st-century-new-deal; https://www.culturalfoundation.eu/culture-of-solidarity

[8] https://processedlives.wordpress.com/2016/10/12/liveability-and-the-black-squat-movement/

[9] https://www.businessinsider.com/spain-universal-basic-income-coronavirus-yang-ubi-permanent-first-europe-2020-4?r=US&IR=T