“Gender is in no way a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts proceed; rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time—an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts.” (Butler, 1988, 519)[*]

“Performativity cannot be understood outside of a process of iterability, a regularized and constrained repetition of norms. And this repetition is not performed by a subject; this repetition is what enables a subject and constitutes the temporal condition for the subject. This iterability implies that performance’ is not a singular act’ or event, but a ritualized production, a ritual reiterated under and through constraint, under and through the force of prohibition and taboo, with the threat of ostracism and even death controlling and compelling the shape of the production, but not, I will insist, determining it fully in advance.” (Butler 2007 [1993], 95)[†]

It’s been quite a while since my last post. Finishing and submitting the PhD around which this blog was initiated very much stepped into absorb all of my writing. Despite still waiting for a date for my viva (another story), I’ve begun to transform the thesis into more of a working model and framework. This has inevitably got me thinking, looking and wanting to write this blog again. If for nothing else to stop me forgetting the constellation of ideas that form around the building of foundations and connections for another project. Another post will follow on the curatorial-research project that I’m working on as the outcome / slipstream of the PhD. However, I wanted to begin (again) with a somewhat fawning placeholder — at least that’s how it starts.

Since I stumbled into it (sic) on Twitter/X the other day, I’ve been periodically obsessed with Russ Garrett’s (https://russ.garrett.co.uk) Open Infrastructure Map (https://openinframap.org).

The platform offers a navigable, zoomable view of much of the world’s infrastructure mapped in the OpenStreetMap database (limited to: Power transmission, Solar generation, Telecoms, Oil & Gas, and Water infrastructures which can be made visible / hidden through a side-tab; and limited to what information is available: power networks being much better covered than gas for instance). Though this information is publicly available — and is already mapped in the OpenStreetMap database, with Garrett’s map just exposing it (https://openinframap.org/about) — what is fascinating is the detail and granularity of both the infrastructure itself and of the mapping representations of it. For example, I can zoom in from the global view of major power transition lines across and between countries and continents to power stations and regional / local power distribution, right down to individual poles on those power lines or the sub-station 2 minutes away from my house and which I pass by most days. (Of course, this map will be limited by available data.)

Putting it another way, the leading story (and analytic) around infrastructure is that is fragile, needs constant maintenance and is invisible — and that it is in fact so locatable (which as a public asset it should be) seems to contract at least two of these factors. The fragility of infrastructure comes from many things, but primarily for critical infrastructure is its materiality and connectivity. Here on this map, its grounded mediating and connective systemic aspects exposed and bare, not secreted away as the popular imaginary has it. This openness belies another point I have sought to make often. That infrastructure is not hidden, it’s just not looked for. In the pursuit of both functionality and, as Thrift put it in 2004 via his reading of Berlant and Butler,[‡] the realisation of our anticipation and expectation of infrastructure through the performance of certain forms and practices which sustain infrastructural operations despite its fragility, it is often useful, if not necessary to ignore the physical, choreographic, processual and protocological aspects of being in, amongst, through infrastructure.

On the one hand, what this map can show is the sheer scale and sunk costs in the infrastructures which determine a huge amount of what it means and feels to live in any situation in which the sharing and distribution of resources and deposition of waste is used in the sustenance of ways of life. Importantly, as Paulo Tavares’s accounts (among others) of indigenous Amazon communities’ forest management practices imply,[§] infrastructure is not a concept that should limited to, or even owned by so-called developed economies and the modern imaginaries on which their power has been built over the last 500 years; such indigenous practices have co-existed with and been supportive of other ecologies for thousands of years. Indeed, as Aborigini Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Elder Uncle Dave Wandin described in Landscape as Protagonist (2020),[**] while Aboriginial peoples may have made mistakes in the 30,000 or 170,000 years (depending on the evidence) that they had been custodians on the land, it had only taken settler-colonialists 190 to make many more hugely consequential mistakes (2020: 13). Moreover, it is the very anti-sustainability of much of the infrastructures of modernity — or what Tsing et al. (2020) call the imperial Anthropocene[††] — that is in fact against the life it claims to support. It is possible to read Fanon’s anti-colonial text The Wretched of the Earth (1961) as in part an account of the abyssal line (qua, Boaventura de Sousa Santos[‡‡]) within infrastructural worlds: “The town belonging to the colonized people … is a world without spaciousness; men live there on top of each other, and their huts are built one on top of the other. The native town is a hungry town, starved of bread, of meat, of coal, of light.” (Frantz Fanon (1961) 39). See also Roitman and Mbembe.[§§] How these other forms of land management might be thought through the lens of infrastructure without detriment to the other, non-destructive ways they are imagined, whilst also contributing to an undoing of the version of infrastructure that Fanon described and which persists, is for another time.

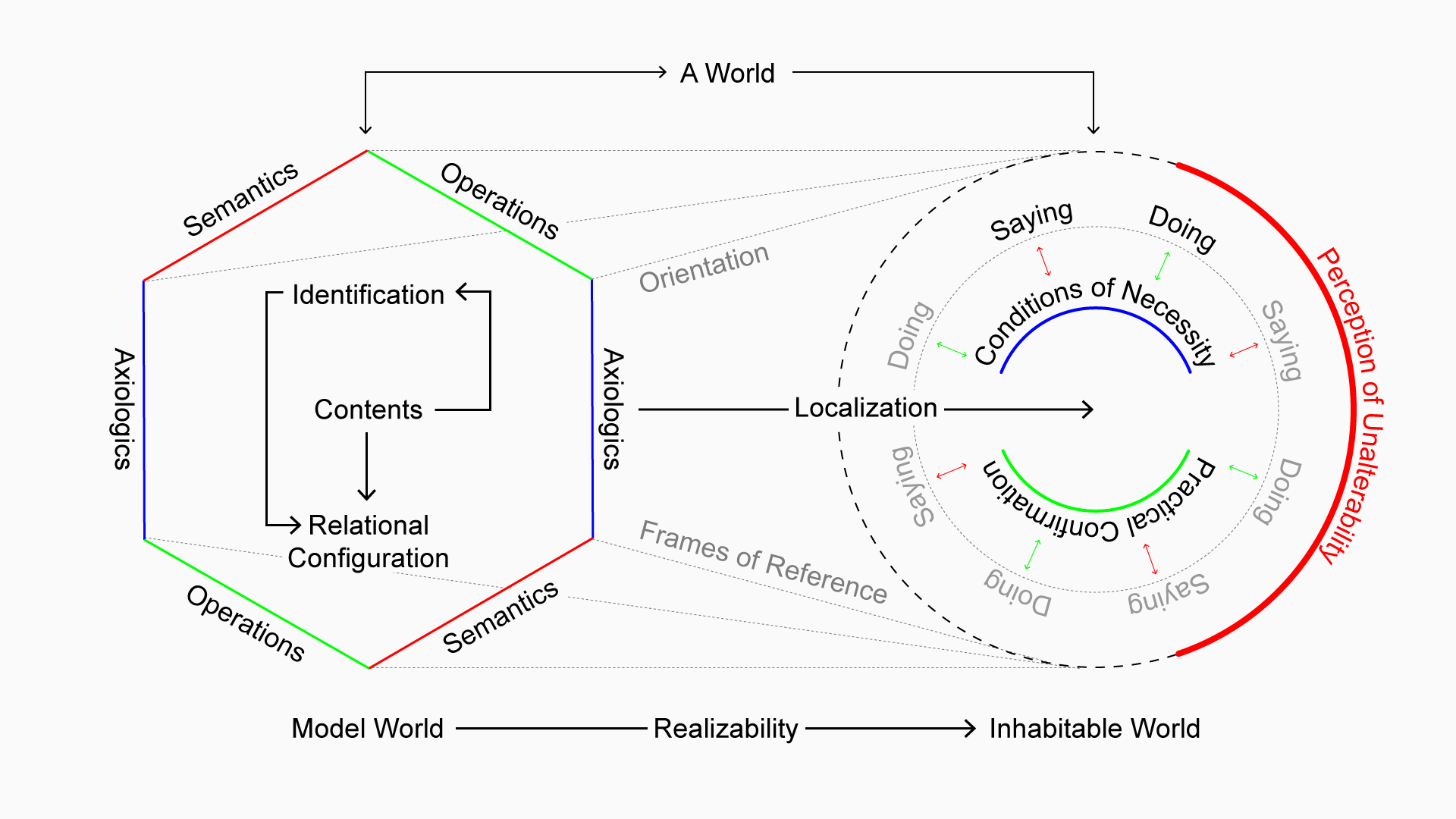

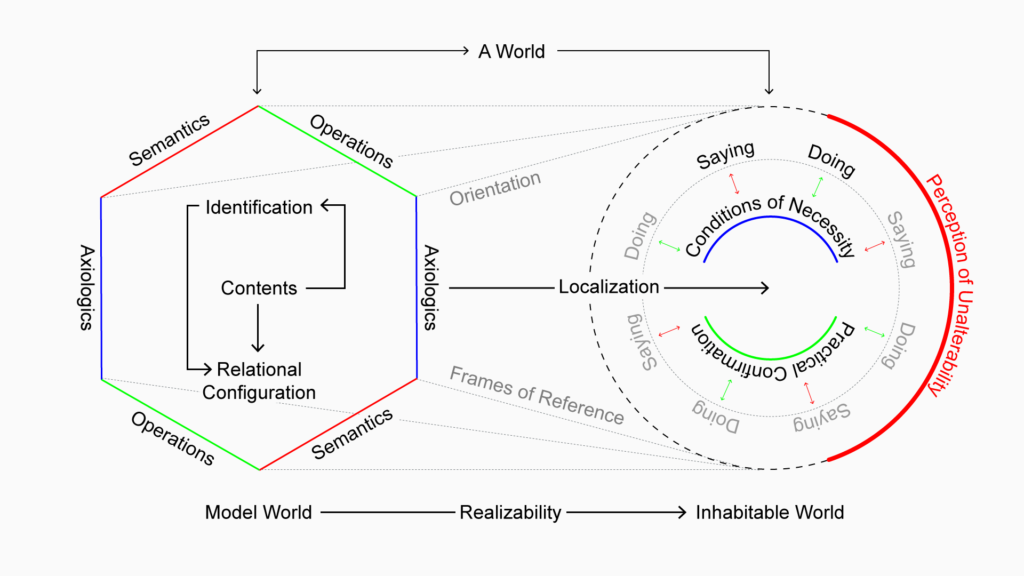

But what this map also allows, in its demonstration of the vastness of infrastructural detail it shows to be integral to a way of life, is another preliminary question: What is the styling of social performativity sunk into the infrastructures this map shows, and which makes one infrastructural worlding destructive and another sustainable? Via Nigel Thrift’s 2004 essay “Remembering the technological unconscious by foregrounding knowledges of position” — in which he explores Butler’s notion of performativity to think through the forms of location, positioning, and juxtaposition necessary to the operation and practicing of infrastructures of addressing, showing how these generate repetition and anticipation of that addressability — the question of infrastructural styling becomes usefully analytic. That is, it can help to see how infrastructural worlds are created and maintained beyond only being structure or process; that is as socio-cultural practices, beliefs, imaginaries, politics and so on (see also Ashley Carse for a good account of this[***]).

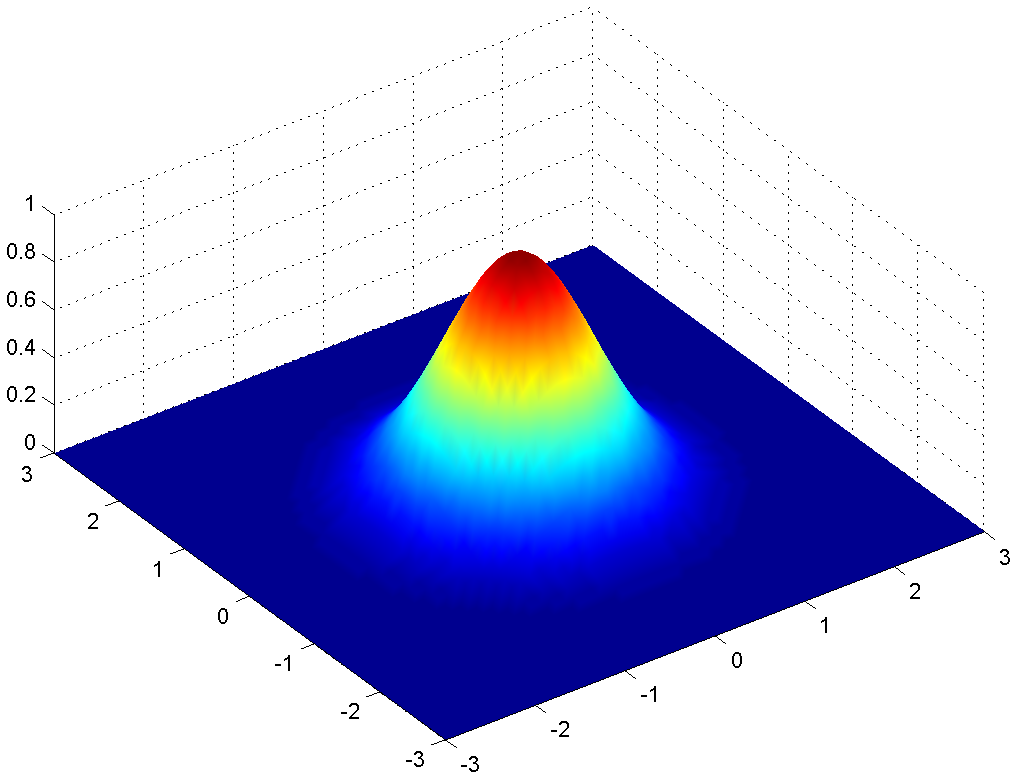

One thing this map does is, in this sense, to document that sheer presence of those infrastructural elements whose layout and needs enforce the styling (as Butler puts it, cite), of multiple actions / actors towards the successful achievement of infrastructural worlds. Just to follow the gas or water pipe lines from a refinery outside of Tamanrasset in Algeria to Skikda, a port on the Mediterranean, or from the Elan Valley in Mid Wales to Birmingham in the West Midlands, and to think of the cost (economic, social, environmental) involved in producing that line, speaks to the fixity of a way of life situated in the urban centres joined by these pipes. It shows the complexity of just one layer of infrastructure required and which is often missing from developer-led housing programmes. But it also shows, in many ways, an old way of life, one which cannot be sustained in present climactic and social conditions of crisis and inequality. Clicking on the solar generation layer offers a hopeful heat map of solar power generation across the surprisingly well-covered islands of the UK. Yet to return to the fixity of other layers, also speaks to the structurally and geographical inequality of the both UK and further afield — something which given the increasingly complexity of post-fossil infrastructure, is exacerbated by the dis-investment and privatization of what should be common assets and services.

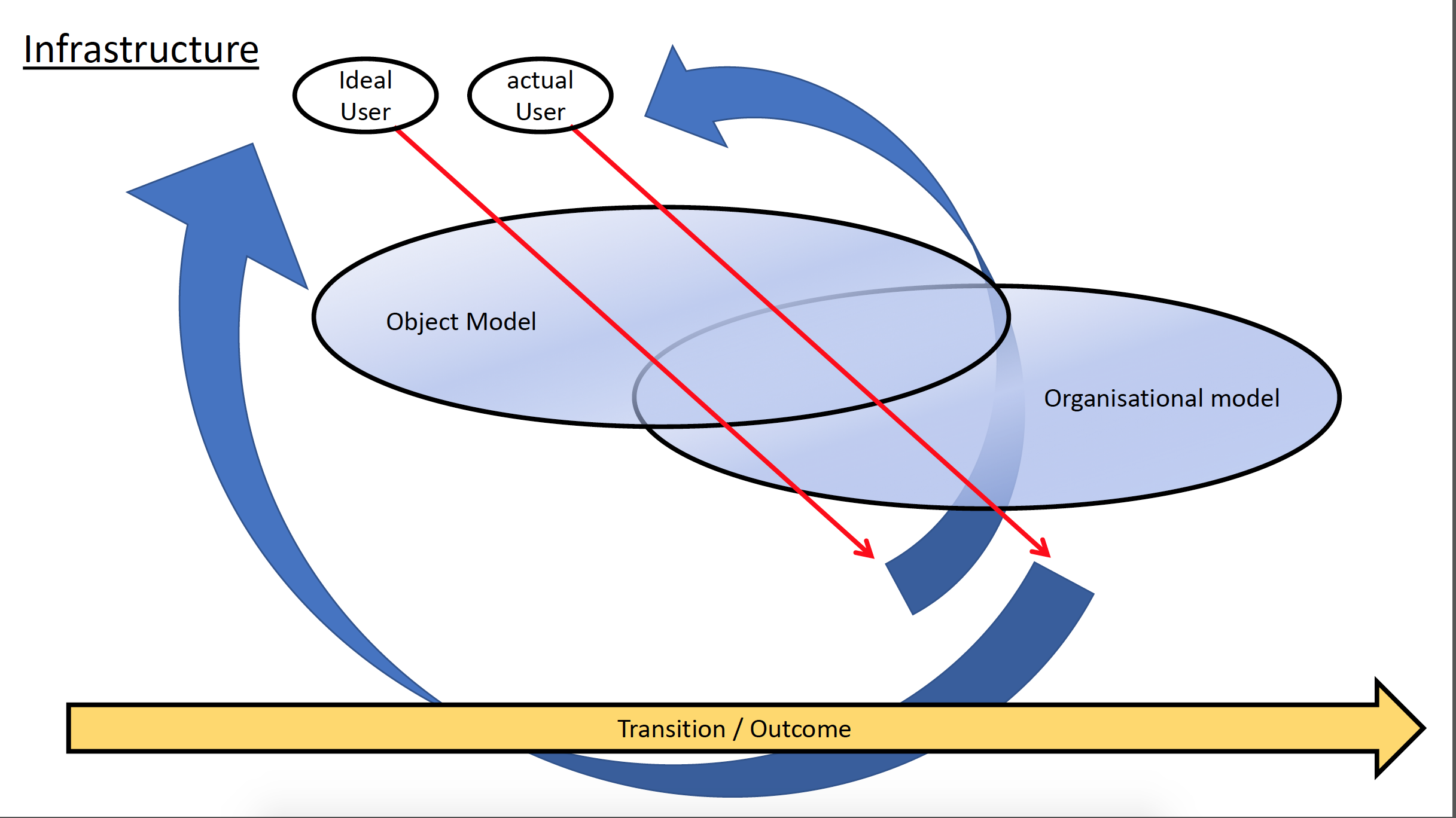

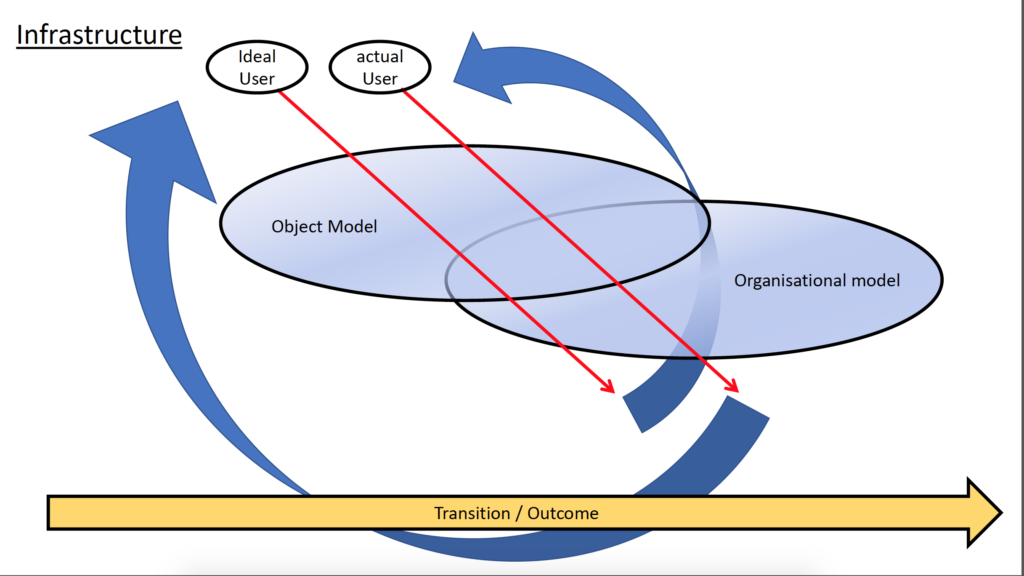

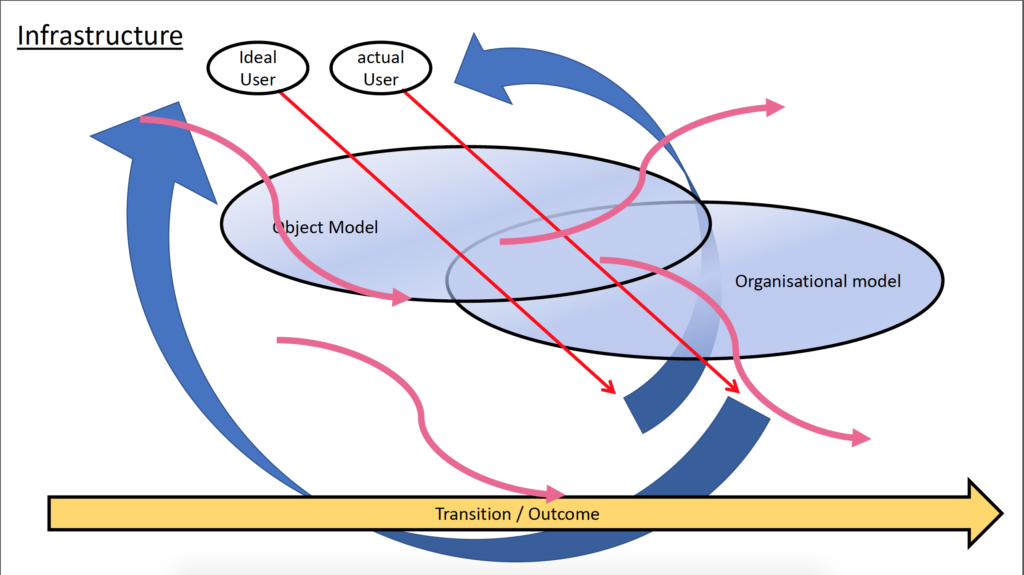

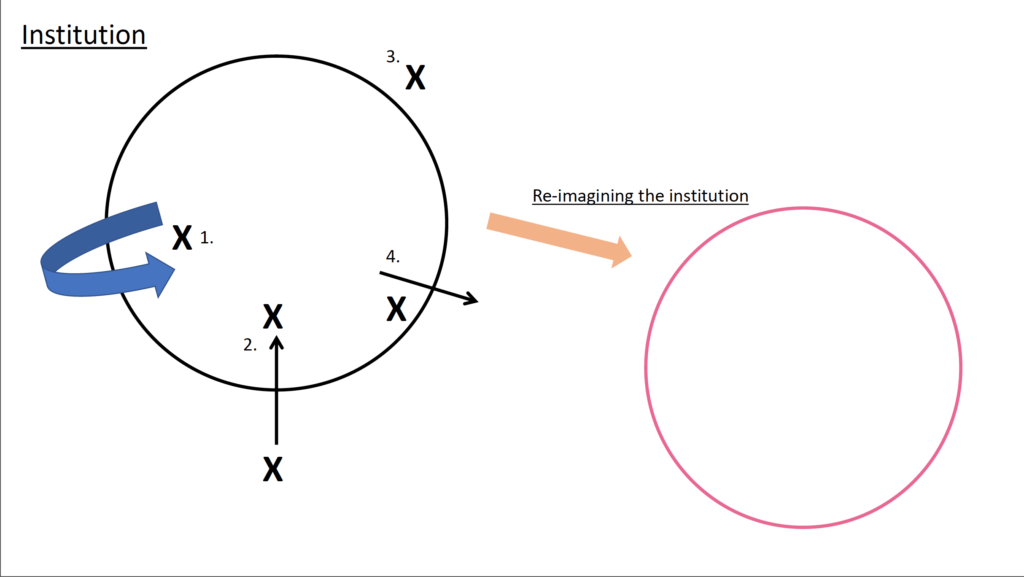

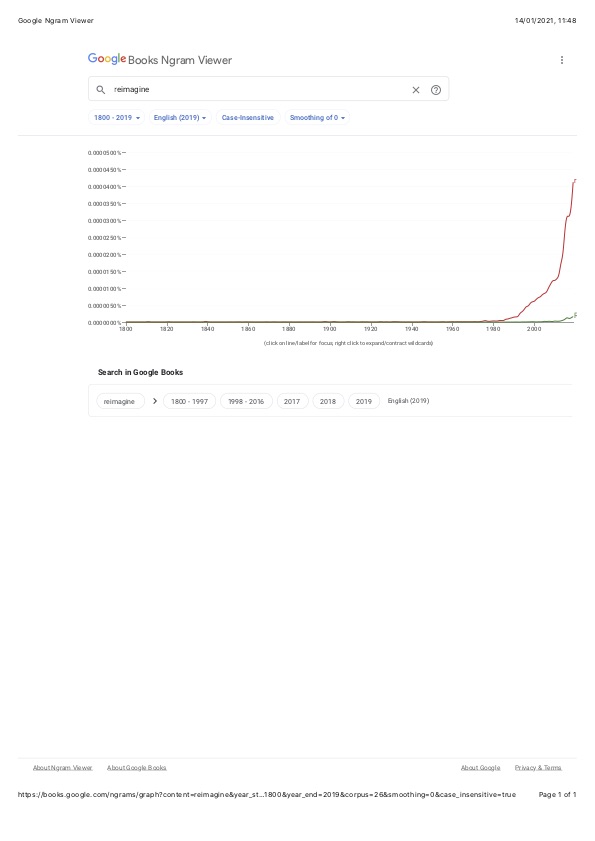

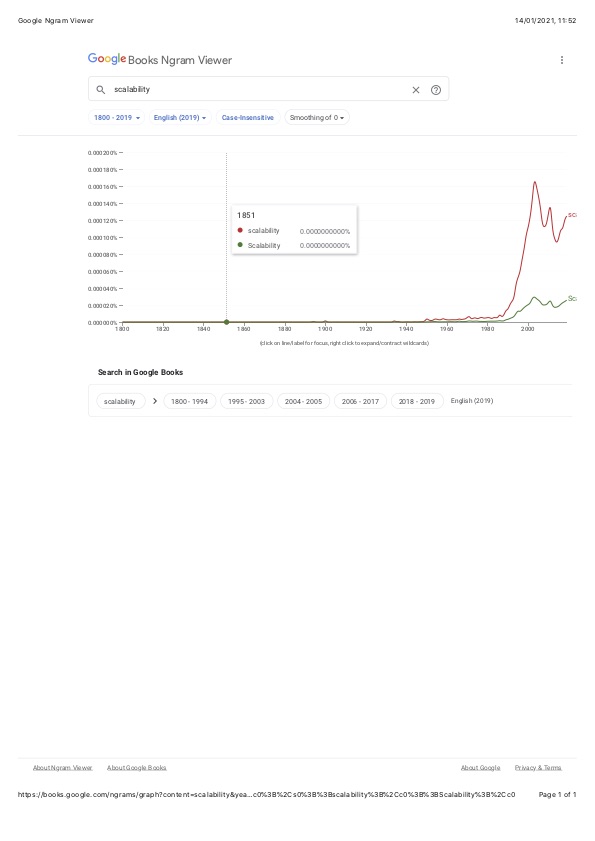

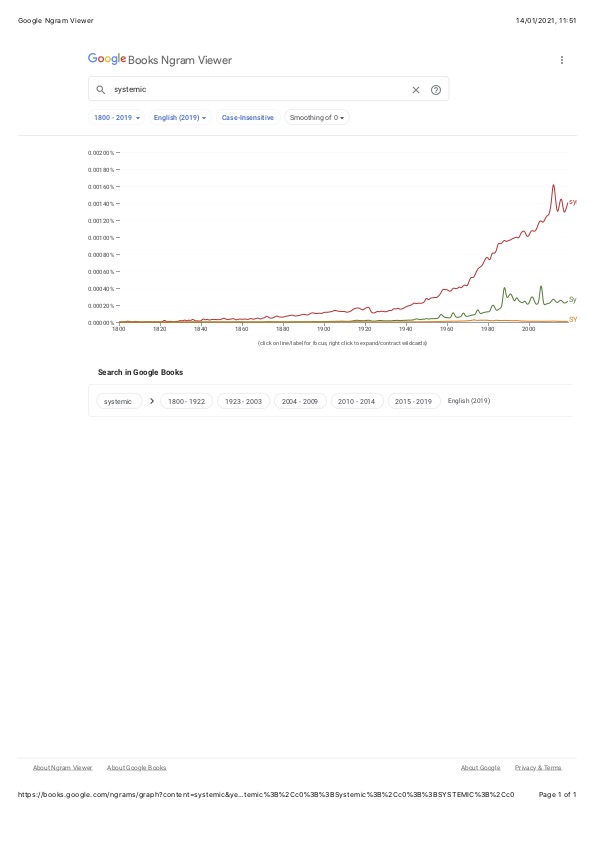

Returning to the map: as I get lost in exploring the what infrastructures are there what becomes clearer and clearer is the sunk costs, the huge resources, actual connections and deep durability that are necessary to infrastructuring, to making a world work in a particular way and to shaping the practices that maintain its relevance. (It’s an obvious statement to point out though the case can be made for something like HS2, the shock of the cost of something that is so relied upon becomes too much for its investment potential to bear.) It is, then, something to bear in mind when using infrastructure as an operative metaphor, speculative or even analytic device. Infrastructure doesn’t come from nowhere, and doesn’t in the sense offered by the Open Infrastructure Map go anywhere fast. However, the point I want to make is about how this information and its visualisation helps to think about the implications of using infrastructure as a capacious and transposable definition, method or speculative device: X as infrastructure. What Rossiter has termed in his exploration of the application of software as infrastructure services into ever more economic and social operations, X as infrastructure,[†††] allows us to think about how infrastructure has become an organisational metaphor that leads the design of ways of life according to software mediated models, with infrastructuralisation and infrastructural practices coming in afterwards to shape the worlds X as infrastructure promises into being.

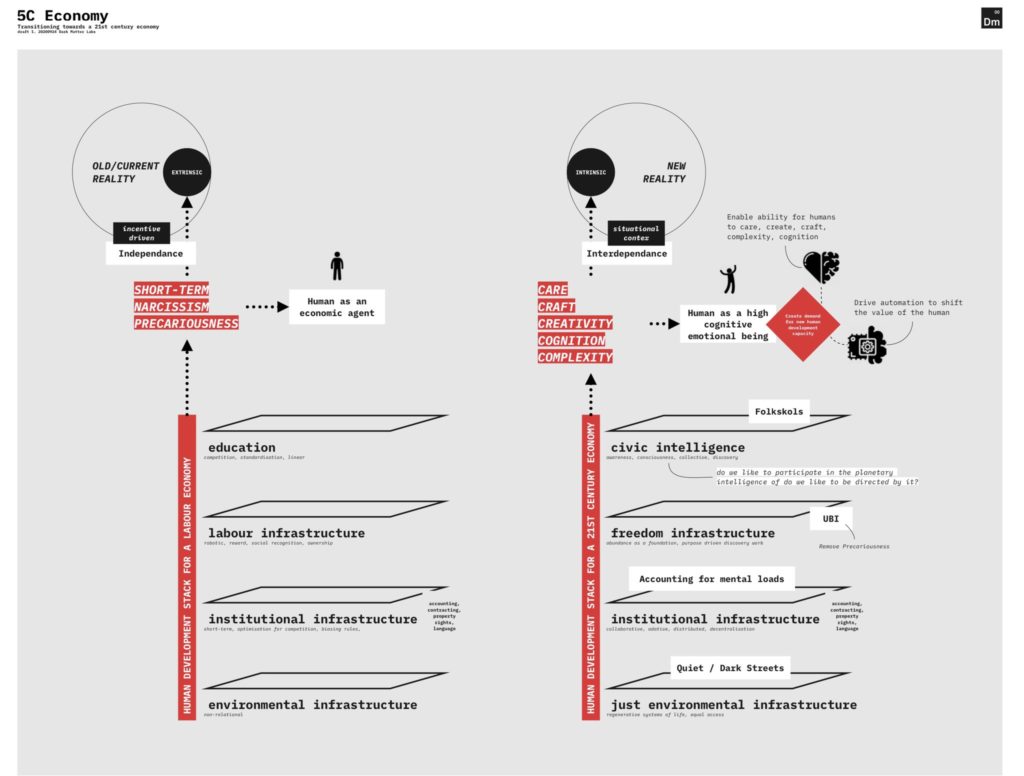

Demanding the styling that conjures, in Butler’s terms, the world and its repetition one must enact in order to appear within the social. What this means is that, as well considering what infrastructure we might need for a particular activity — such as culture — we think of infrastructure as a particular kind of approach, form, genre or possibility, with specific kinds of practice, choreography, methods, duration and assemblage possible and necessary because of how infrastructure is made and what it does. This is a powerful approach, with downsides, such as the automation of social services that should incorporate nuance such as benefits decisions (See Goffey), and upsides such as climate modelling and forecast-driven policy making which is only possible as an infrastructural image; and once it’s possible, its’ also possible to use this to integrate new kinds of practice in that assemblage that made this image (see: Bratton, Koinor, Clark)[‡‡‡]). (This is something I will be exploring in my own work, specifically in relation to what curatorial practice, or the ideas of making public / public making are once we use an infrastructural frame.) On the one hand, then, this implies that there might need to be a serious commitment to duration, durability and extensibility when using infrastructure as a guiding idea and mode. There is, however, another way that we can think about this — layered into this map too. That is the radical transformation — or extension — of infrastructure through its virtualization and digitization.

The virtualisation of infrastructure, in particular through software as infrastructure, the creation of digital models that map human activities and which can steer these (see the National Infrastructure Commission’s digital twin,[§§§] algorithm-driven traffic management,[****] advertising-surveillance algorithms, etc.), and computation stacks, as well as the prevalence of what can be called real time, infrastructural images (Konior) in how C21st societies are known, sensed and organised (in urban as well as agricultural and wild settings — see: waste water monitoring, or hedgerow mapping for example: https://twitter.com/woodlandbirder/status/1661442468796137491), have radically expanded and unmoored what can be counted, experienced and deployed as infrastructure. To be sure, and before going on, of course the physical infrastructure of connected, digital and computational technologies and the data moving in them is vast, and shares the remote proximity that makes any infrastructure a weird encounter. And of course these infrastructures are layered onto existing, hard infrastructures. But there is a constitutive difference in virtual infrastructure that is both important to understand and use, if we are to move from the firm ground of power transmission to the generative and dynamic models of alternative infrastructure, the Open Infrastructure Map by rearranging the visibility of these forms is a version of.

The term virtualised infrastructure can refer to explicitly virtualised infrastructure, as with computational stacks. A stack describes the hardware and software and server space and computation required to run a particular application, platform, or service; because services, like an online image editor or map do not only require physical infrastructure like a computer, but also collections of interoperating code and data, these services also run on a virtual eversion of infrastructure. This includes the code, the allocated computation memory and data space necessary to make that run. Moreover, this set up allows multiple virtual infrastructures to be copied, run as tests, and allocated to available space, not fixed in one spot. This has allowed for powerful fungibility and expandability of computational services and processes. Since it means one company can run their services relying on the capacity of another such as AWS and access infrastructure way beyond their own physical capabilities. Another way to think about this virtualisation and which is enabled by these previous definitions, is the application of data models as representations and ways of organising space, time, action, policy and so on. This later case, which draws on the abilities of ever-more powerful computation to model and simulate more complex aspects of the worlds they represent, often providing a different kind of service such as logistics or resource management, through this means that infrastructure in general can become a virtual one, if not integrated into these.

Along with digital infrastructure — which might include the digital twin (a live and dynamic model of national infrastructure, NIC), social media drive cultures and communities of communication, or locative-embodied sensory mobile platforms and devices more generally[††††] — infrastructural virtualisation can be seen as an extension of the longer histories of infrastructuralisation in X as a service (Rossiter), and more poignantly, the rise of international and national governmental, corporate, and non-governmental policy and regulation.[‡‡‡‡]Aside from the pseudo-stance of anti-regulation in free market cheer leaders, this is a history of the re-working of a deep reorganisation of the economy and social organisation around the protocols of financialisation, insurance, management standards, consultancy, software and platform integration, the think tank complex, and so on,[§§§§] — enabling and consolidated what was once called neoliberalism, but is perhaps more akin to a platform-rentier-extraction hybrid. Both, nonetheless, constitute, I argue, a shift from the institutional, corporation or even multinational model of social, economic, political and cultural organisation to the infrastructural. That is one in which the practices of performativity that constitute accepted forms of life — and therefore entry into rights holding, or care/service-access — are not concerned with discrete symbolically-determined arenas or institution that act as coordinates within the symbolic-psychic territory of a social / cultural group. Rather it is the performative that sustains the relationships, connections, movement and mediation between these coordinates — practically, conceptually, speculatively. It is the lines of the diagram that exist in the embodied experience of being embedded in the time and space of a moment. It is the feeling and choreographing of the possible.

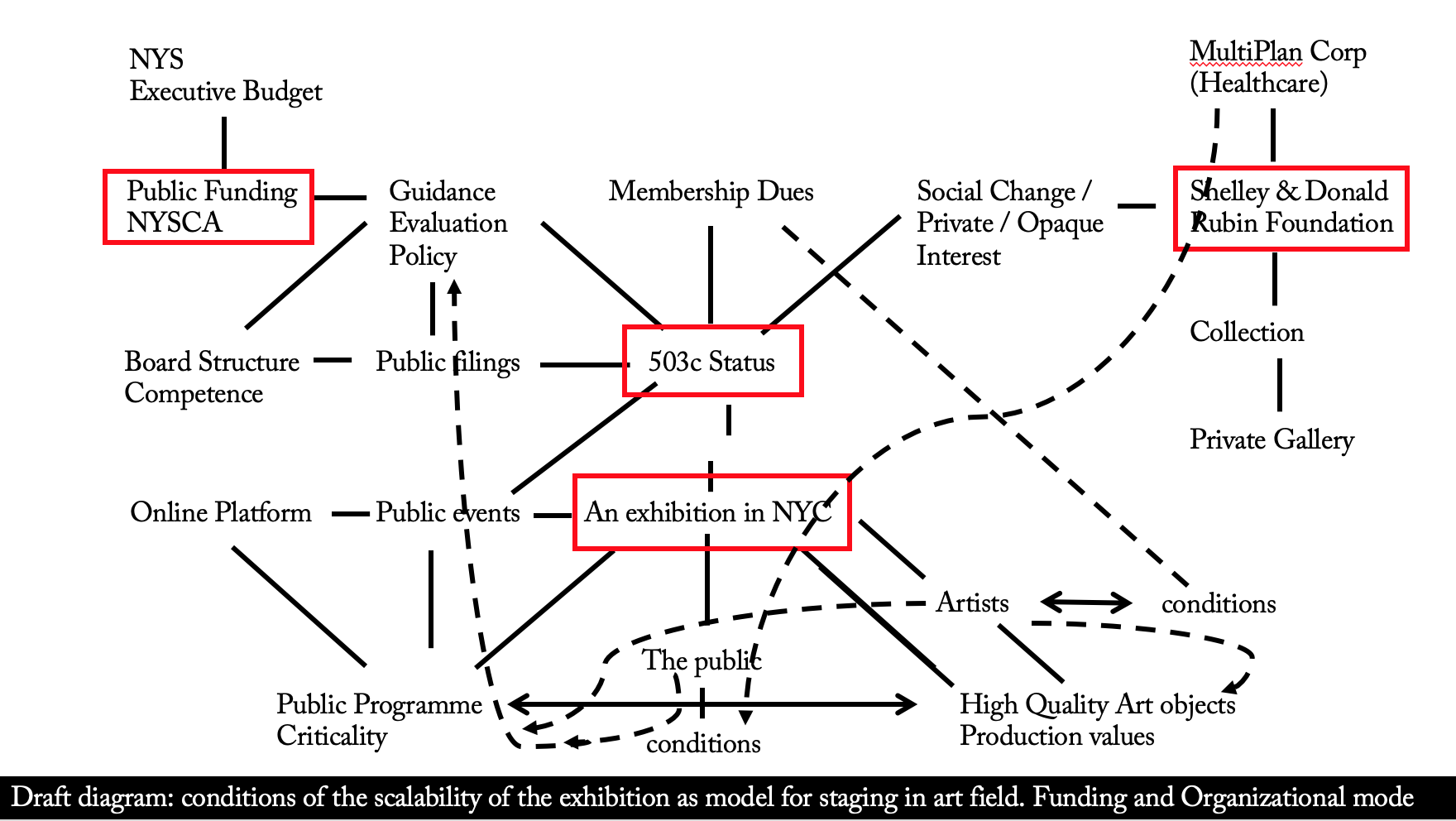

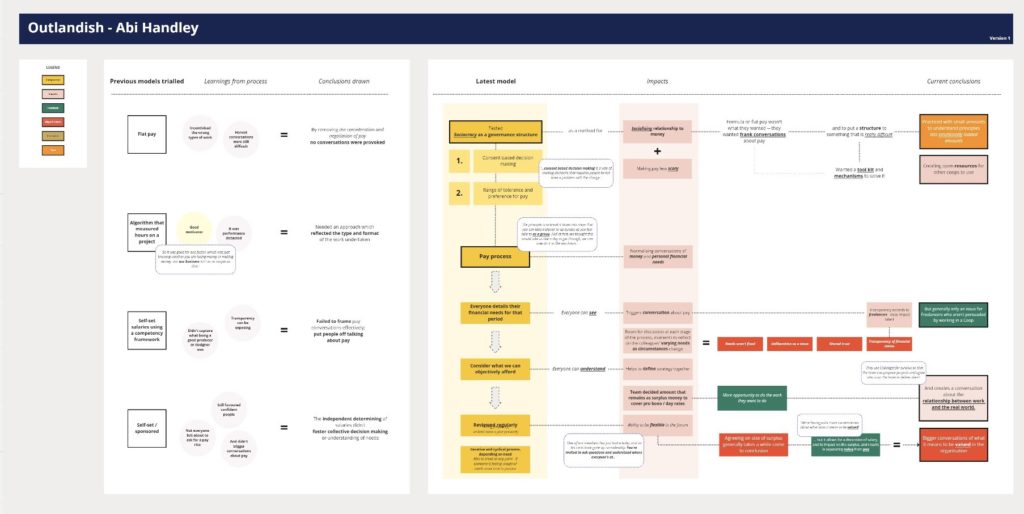

(Solar generation heat map)

What we might call infrastructural control is therefore, something which, via its virtualisation as a kind of abstract picture that acts on, in and as reality,[*****] can extend the relational, distributive and elusive but consequential from of infrastructural control way beyond what is imagined in bridges, power lines, roads and even data centres. Infrastructural control shimmers poikilos-like,[†††††] but bears down with all of the weight of its totality. But in its contrast to the seeming lightness of being of digital or virtual, what the OIM makes visible in the sheer vastness, extent of critical infrastructure is the work which must be done to establish any alternative. Digital and virtual infrastructure promise a disruptive flexibility. Of course, this is itself built atop a huge infrastructure layer — seen in the power distribution and production and communications infrastructure shown in the OIM. And where digital or virtual infrastructures themselves create ever-more problematic and coercive models of control or the reproduction of biases they treat as foundational in potentially destructive commodified emergent cognitive intelligences in AGI / LLM, at the same time as being important forms through which complex modelling of climatic forecasting and resource allocation that could abate current states of ecological collapse, or way which alternative communities of practice can build,[‡‡‡‡‡] there is a tension to be exploited in the work of infrastructuring. Any alternative requires the (infrastructural) work to be put in; an alternative needs to create the same impression as the OIM does if it is to take on the load given to extant infrastructures. If infrastructural performativity is the surface that sustains repetition of all sorts, to look and think about what OIM shows us is to think and imagine the forms, signs and stylings (to borrow form Butler) that might constitute such a space of making happen.

So, though the Open Infrastructure Map might create the impression of a separation between infrastructure types by kind; the analytical / critical point is to consider what layering and interfaces between layers might be necessary as sites of strategic and operational cooperation, mediation, tension and halting in the flow of information and actions. What is at stake is the possibility of alternatives, extensive ways of living, and wresting this public space from actors not interested in common life. In the necessary but complicated need to accept the artificially of any survival of climate change (I agree with Benjamin Bratton in the Terraforming this much), we need to think through this durability and granularity and sunk styling of the alternative infrastructure. While this began as a simple reflection on the enjoyment of seeing what is already there in a new light; but the sunk cost and sunk styling it implies need not only be an impediment to systems change, but a guide.

[*] Butler, J., “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory”, Theatre Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Dec., 1988), pp. 519-531

[†] Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Routledge Classics. New York; London: Routledge, 2007.

[‡] Thrift, Nigel. ‘Remembering the Technological Unconscious by Foregrounding Knowledges of Position’. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22 (2004): 175–90; Berlant, Lauren. ‘Trauma and Ineloquence’. Journal for Cultural Research 5, no. 1 (2001): 41–58; Butler, 2007.

[§] https://www.bakonline.org/program-item/human-inhuman-posthuman/forest-law/boven-de-puinhopen-van-amazonie-koloniaal-geweld-en-de-koloniaal-verzet-langs-de-grenzen-van-klimaatverandering/

[**] Donse, S., Landscape as Protagonist (Collingwood: Molongo 2020)

[††] https://feralatlas.supdigital.org/

[‡‡] https://blogs.akbild.ac.at/dispossession/glossary/abyssal-line/

[§§] Mbembe, Achille, and Janet Roitman. ‘Figures of the Subject in Times of Crisis’. Public Culture 7, no. 2 (1995): 323–52.

[***] Carse, Ashley. ‘Nature as Infrastructure: Making and Managing the Panama Canal Watershed’. Social Studies of Science 42, no. 4 (2012): 539–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312712440166.

[†††] Rossiter, Ned. Software, Infrastructure, Labor: A Media Theory of Logistical Nightmares. New York: Routledge, 2017.

[‡‡‡] Bratton, Benjamin. The Revenge of the Real. London: Verso, 2021; Konior, Bogna. ‘Modelling Realism: Digital Media, Climate Simulations and Climate Fictions’. Paradoxa 31 (2020 2019): 55–75; Clark, T., “Restaging Infrastructural Images That Make the World: Reconfiguring Scale” chapter in El Baroni, B., Between the Material and the Possible (Berlin: Sternberg 2021).

[§§§] https://nic.org.uk/app/uploads/Data-for-the-Public-Good-NIC-Report.pdf

[****] Hayles, N. Katherine. Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 2017: 122

[††††] Farman, Jason. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. New York: Routledge, 2012.

[‡‡‡‡] Easterling, Keller. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London?; New York: Verso, 2016.

[§§§§] See: Rosamond, Emily. ‘Shared Stakes, Distributed Investment: Socially Engaged Art and the Financialisation of Social Impact’. Finance and Society 2, no. 2 (2016): 111–26; Easterling, 2015; Rossiter, 2017; Khaili, L., “In Clover” London Review of Books, Vol 44 no. 24, December 2022; Srnicek, Nick. ‘Nick Srnicek • Platform Capitalism’. Lecture presented at the MFA Fine Art and MFA Curating Lecture Series, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, 6 February 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bYCiUEB7kyg; Lee, Pamela M. Forgetting the Artworld. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2012.

[*****] Cf. Vishmidt, Marina. ‘Beneath the Atelier, the Desert: Critique, Institutional and Infrastructural’. In Marion von Osten: Once We Were Artists (A BAK Critical Reader in Artists’ Practice), edited by Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017.

[†††††] https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/????????

[‡‡‡‡‡] Star, Susan Leigh, and Karen Ruhleder. ‘Steps towards an Ecology of Infrastructure Design and Access for Large Information Spaces’. Information Systems Research 7, no. 1 (1996).