Story telling, or narrative accounts of the relationships, often complexly layered, increasingly constitute our understanding and experience of being ecologically and technologically embedded.

All the discourse and jargon that goes with that, systems, etc. And I said to them, but where do you see that system empirically? Show me where you see that.

So what are we talking about? And so you get them to rethink the paradigm with which they’ve come in, and get them to start piecing together what they see. Tack from the macro to the micro, the other way around, start with the micro, and situate that, situate, situate, you’re situating everything.

And so it becomes this process of connecting. And that’s incredibly empowering to see people begin to be able to do that in their own worlds and with their own life experiences.

These are really powerful moments where African students, graduates, can engage with theory and both speak back to it and say, yes, this fits, but no, that doesn’t fit. But also fundamentally experience that the way that the environmental humanities work is often written in the storytelling mode. I’m thinking of Tom von Duren’s work, for example, Donna Haraway’s stories, you know, tell stories that take you in to the big picture, that enable you to speak of, you know, the macro in relation to the micro

Lesley Green, Multispecies Worldbuilding Lab: Lesley Green – Part 2, 26 Mar 2021

By connecting and encapsulating multiple dimensions, entities, events and temporalities in situated, non-complete forms, narrative and story telling are key tools in the visualisation, research, analysis and public communication of the depth of relatedness, causality, inheritance and web of effects and consequences that make up long durational often human-induced/affected phenomena such as the Anthropocene or eco-systemic equilibrium. Phenomena that, like narrative, constitute our worlds as much as being produced in or by these worlds.

Narrative and story telling allow conceptual shifts in scale, diagrammatic connections, illustrative actions, focus to be drawn across dimensions, metaphor, simile and description etc., to all function as epsito-ontological devices; devices that cohere in a secondary form what cannot be seen all at once. I’ve certainly been attracted to the idea of narrative, a methodological and epistemic mode that has been increasingly used to navigate, communicate, and often critique the complexity of contemporary infrastructure. But at the same time, a turn to story telling when discussing infrastructure in its environmental, human context, can naturalise the closure of infrastructural promise, practice and repetition. Why, specifically, is it important to consider the consequence of the tools or methods by which we know, analyse and transform our world through infrastructure?

Infrastructure turns.

There has, undoubtedly, been an infrastructural turn. The term appears much more often that it once did. Whether this be the rise in the use of the term; in the spread of infrastructure projects driven by technology and climate adaptation; the creeping infrastructuralisation or consolidation of public resources into the vast portfolios of private equity and asset managers; or the realisation that while neoliberal (and now authoritarian) policies may have extended legal and economic infrastructures in the capture of resources, they left public and social infrastructures for dead. The infrastructural turn is as much a realisation that infrastructures need rebuilding and reclaiming — from local government, housing, in the arts and in the architectures of truth making, as it is a reflection of the priorities of societies, governments and in cultural and academic practices reflecting on or researching this.

Infrastructure is not, however, an agnostic term, which is key. Much work has been done to invert, surface and denaturalise the actually existing edifice of infrastructure. But as Dominic Davies persuasively argues (2023), infrastructure is not simply a physical or operational system but a specific semantic, symbolic, and culturally-significant entity. That is, it is, in contrast to public works, a term which took the place and role of infrastructure before the massive investment and rebuilding of countries after the second world war, infrastructure is deeply wedded to economy. That is, it is a term and entity that can be and is read through the lens of its economic metics, such as infrastructure as an investment, a measure of a countries domestic product, as a means towards an economy. Of course this is not all an infrastructure is or means; but it is a powerful constraint on what it does, and in what is referred to when, in many fields, infrastructure is turned to.

The use of narrative reflects an attempt to both join the dots between the unfamiliar, complex, and multi-layered realms, dimensions, events, and actions that constitute ecologically and systemically aware and embedded realities that are understood to be the setting for life today; and to situate these encounters or experiences within and as culturally-situated phenomena. This situating might be in time, place and environment; but it is also to situate the story teller and reader, the knowledge, the prompts, inheritances and connections within which they embark on infrastructural encounters.

To embed a concept of reality through narrative to interpolate who ever is on the other end of that conceptualisation into what Lauren Berlant called the historical present (2001) — the affective experience of being embedded into all that shapes each moment of that experience as how and why history unfolds as a series of localised instances. Narrative recreates or conjures, diagrammatically and metaphorically the deep range of factors that constituted a lived reality. In this case, narrative surfaces the various factors of an infrastructure we might only passingly acknowledge or know in use; yet through the use of which we become part of a much bigger dimensional space and setting. For instance, to use the internet is depart from the space-time of the telegraph, the geological or extra-planetary space of energy use, the colonial-material dimensions of mined hardware components as well as the micro-macro time space of global connected computation, and the future-oriented anticipation of using the web for a specific purpose. These can all be encompassed within the expanded narrative of me sitting down at my laptop to write this blog post, in part to hold in place thoughts for later research, in part to get back into the habit of writing — if only to improve it.

More conceptually, this urge to situate accounts of reality within the historical present might be said to respond to a number of factors. These include, the expansion of human activity into a geological and ecological dimension and consequences, with terms such as the Anthropocene, the more than human, etc; to the deepening and broadening of historical perspectives and legacies to incorporate the other sides of histories of empire and colonisation and the ongoing inheritances of these; the pluralisation of imagined communities and disassembly of institution of truth and fact through the interconnected rise of increasingly complex simulation and communications technologies and geopolitical reconfigurations around these networks and economic infrastructures increasingly centralised on the demands of financial (and private equity) and technological infrastructures (see Brett Christophers, 2023). In short, to the material, discursive, cultural and social implications of the infrastructural turn. And here I mean the infrastructural turn in its wider sense, not just in academic or artistic discourse and practice (as Harney and Moten might argue). But rather, in the ways that certain kinds of infrastructural logics — economic assets, digitally-modelled, scalar, productive, etc., — are infused and diffused into more and more of the how human life and its consequences or interactions with more than human realms unfold, repeat and are imagined. (I.e., where increasingly, Benjamin Bratton’s 2015 argument that the Earth has become an (accidental) computational megastructure or stack, feels less fanciful and boosterish and more politically analytical.) Narrative bears a heavy weight in the context of conceptualising infrastructure and cultures build on, around, through and for it; a freighting that bears further analysis.

Narrative infrastructure

As many argue, narrative acts in such systemically complex and dynamically-experienced contexts as a framing device. It allows us to account for and assemble coherence within these settings. A coherent account of moving through, being affected by or affecting that assemblage, or of accounting for what is not immediately or routinely seen. Here narrative, as Mieke Bal would put it (1999), is a motor to stitch seemingly disparate parts together into something meaningful. There is more to be said about how we got here. This includes, what might be called a post-post-modern situation in which there is a technological and philosophical imperative to bring coherence back to the fragmented narratives and truths the post-modernists alerted us to, and which are both multiplied and fought against through the individuated self-storying of social media; and of the return of meta narratives simultaneously with and without a strong relationship to the future such as climate change and AI (see Johnathan White, 2024). There is also the use of fiction as a speculative device in art, philosophy and visual culture — aimed against the closure of the future through financialisation or indeed climate modelling (Reeves-Evision, 2021; Sullivan; Konior, 2019).

But the main purpose of this post is to note down two other closures with respect to narrative and to infrastructure. Namely, that the term infrastructure, while key to thinking about conditions of possibility, may be in effect so socially and historically specific that it equates to a closure of those possibilities of a vast array of conditions of collective coordinated activities, resource allocation, co-produced and experienced forms of meaning, sensing or energy exchange. And following this that, connectedly, it may be that narrative, or at least certain kinds of narrative are part of how that version of infrastructure and its limitations are being fixed in place or repeated.

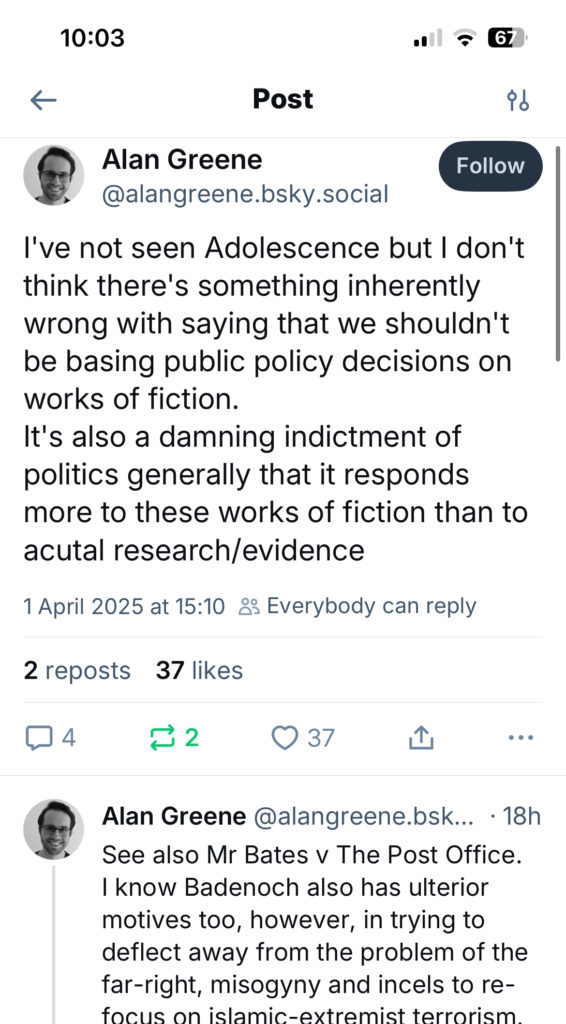

(1 April 2025, https://bsky.app/profile/alangreene.bsky.social/post/3llr2ghagzk2s)

As this post from a Bluesy user indicates, narrative has been centred in accounts of public truth, to the extent that it might even replace other modes of evidence. It is not just a more accessible form for articulating how things go together and unfold in time. Moreover, could it be the case that the construction narrative as a social and individual device of meaning making is so embedded into the infrastructures of contemporary reality (the feed, storify, constructed reality, social media as affective, epistemic and sensory prosthesis), and in forms that have centred local, individual, partialised narratives that it is no longer useful as a hermeneutic, critical, aesthetic and political device? At least from the perspective of getting to verifiable, common, or evidence-based truths — and in building or instituting meaning in common or truths around this?

In part, I think the answer comes from addressing the prevalence and enclosures of the terms infrastructure and narrative, or at least defining how they are used and framed currently. That narrative as often constructed and experienced — in a temporally linear mode (listening, reading), semantically complete (completed by present of teller / receiver), coherent (in its own terms), inclusive (of its constituent parts), performative and metaphorical (scalable on a human basis — i.e., lessons, prompts, accounts, rules on human experience or behaviour), or durable speaks to inheritances of imagined and institutional forms of meaning (see Castoriadis, 1987) whose integrity as evidence is based on reproducibility rather than errancy in the setting of its telling and re-telling. To begin with I’m thinking about the institution as a long-duree form for maintaining certain narratives of purpose and value in forms that exist beyond the life world of individuals as in the case of Monasteries (Pottage, 2014) or social imaginaries (Castoriadis, Ibid.); I’m also trying think of this long-duree formation of narrative closure in infrastructural terms — as well as its rupture in these terms. But this means paying attention to how narrative functions like an infrastructure, in relational, systemic, subordinate or at least intra-positional modes as opposed to supra-positional forms like institutions.

For instance, in the academic setting, narrative or testimony of an interviewee in an account of experience or event must be treated as a sacrosanct document which must not be altered in order that it is accepted into the analytic frame; which then seeks to uncover meaning from that testimony so that neither the original testimony and the methodological approach or environment of the telling and re-telling are unchanged too — i.e., unexpected variability is closed off.

In conspiracy stories, a semi-permable world / story is created; it’s persistence is determined by the ability of the narrative to selectively incorporate new information within its parameters; excluding or incorporating contractions as not relevant or as proof of the need for hermeticism to protect the truth against the subterfuge of other evidence.

Similarly, in tech the so-called weird is often invoked to describe that which appears within a complex model or system but which cannot be explained within its stated narrative. While the weird is often seen as a potential site of novelty or aberration, it must also be understood as a a function of a wider, if not fully understood closure by complex computational model infrastructures; a narrative bulging not a shift.

In the context of more familiar social and economic infrastructures, narrative can function as a further enclosure; for instance the idea and story of the big society (David Cameron-era Conservative UK government), where members of a society each play a role in keeping that society cared for and in motion, taking up what the state had or should have done, in fact allowed for the re-cohering of soft infrastructure at a much reduced level. It re-enclosed the terms of social life within the re-parametricised terms of austerity.

(Another limit to consider is that narrative can often work best with a protagonist. This complicates the multi-perspectival aspects of infrastructure and its relevance to those perspectives (see Star 1998).)

Now on the one hand this implies that narrative as analytic (and I include narrative research devices like walking in this) might also replicate the infrastructural form, including its closures, at study in ways that might in fact redouble or reproduce the kind of effect of concern. But this also has implications for the kinds of practice we might one to initiate in response. If we want to transform our world — stories and narratives must act more like the things we are seeking to describe or align and attune with or to (e.g., Gaia, sustainable balances of eco systems; gathering and dispersal; plural possibilities of being and identification, etc.,), and take a more critical view of how a tools for visibility or analysis like narrative work already as part of and towards the closure of existing structures and systems.

Narrating an otherwise

In good faith, we talk about the need for infrastructure where it is lacking. Or else, are concerned with who is a stake holder, who is affected, or what. Or what is the objective and what is the means of that infrastructure? But, in each case, does infrastructure simply remain an abstraction or automation achieved through organisational techniques or infrastructural work (see Carse, 2012) that is simply too repetitive and constrictive, scalable (see Tsing, 2012), to achieve flexible or alternative aims necessitate by the new kinds of story discussed above? Do we need to think about what is after ‘infrastructure’ practically, conceptually and in terms of cultural/communicative forms? What kinds of narrative are necessary to this? How do we go beyond the value of narrative that reveals something about the underlying, unseen, inderterminate and abstract aspects of infrastructure to a narrative that reconfigures these forms of shared world building and sustaining objectives and means?

I want to suggest that the kinds of story that must be told to achieve this — i.e., where stories are part of public making in the wider sense — must be janus like, shimmering narratives. That is, to both make use of the infrastructural and the be able to live after infrastructure, in open-ended rather than closed futures, narratives must fork or bifurcate: intensifying some dynamics, halting others; causing coherence collapse whilst also carrying on as a support structure for other kinds of life.

If a conspiracy theory can be destabilised by creating a new perspective within the logic that goes so hard it eradicates base foundations — asking those who believe the moon landing is faked, that they believe in the moon; or MAGA world which part of the Epstien conspiracy is fake — then building intensification into excluded or edge stories might be a used crack in the closure of extant infrastructural narratives as well. For instance, how bringing in more energy into the city might help solve the ecological / climate crisis, by allowing for more re-use and re-cycling of resources, as Tim Lenton argues in “Gaia Devices for a High-Energy Solar-Powered City” (e flux Architecture, September 2025)

In the curatorial space, perhaps narrative modules might allow intensification or bifurcation within the wider cultural infrastructural stacks within which curating participates and performs. This is to be developed.

x

References and credits.

Anna L. Tsing, ‘On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales’, Common Knowledge18, no. 3 (2012): 505–24.

Alain Pottage, ‘Law after Anthropology: Object and Technique in Roman Law’, Theory, Culture & Society 31, nos. 2–3 (2014): 147–66, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413502239.

Susan Leigh Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’, American Behavioural Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): 377–91.

Benjamin Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (MIT PRESS, 2015).

Bogna Konior, ‘Modelling Realism: Digital Media, Climate Simulations and Climate Fictions’, Paradoxa 31 (2020 2019): 55–75.

Brett Christophers, Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World (Verso, 2023).

Cornelius Castoriadis, World in Fragments: Writings on Politics, Society, Psychoanalysis, and the Imagination (Stanford University Press, 1987).

Dominic Davies, The Broken Promise of Infrastructure (2023) London: Lawrence Wishart Press

Jonathan White, In the Long Run: The Future as a Political Idea (2024) Profile books

Lauren Berlant, ‘Trauma and Ineloquence’, Journal for Cultural Research 5, no. 1 (2001): 41–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/14797580109367220.

Mieke Bal, ‘Narrative inside out: Louise Bourgeois’ Spider as Theoretical Object’, Oxford Art Journal 22, no. 2 (1999): 101–26.

Susan Leigh Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’, American Behavioural Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): 377–91.

Theo Reeves-Evison, Journal Article: ‘The Art of Disciplined Imagination: Prediction, Scenarios, and Other Speculative Infrastructures.’ Critical Inquiry, Volume 47, Number 4, Summer 2021: 719-748 – https://reeves-evison.co.uk/The-Art-of-Disciplined-Imagination

Top image: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cold_Fell_(Pennines))