How to think beyond the rationalised / rationalising frame of infrastructures as they are generally characterised from systems perspectives?

Speaking on the Talking Politics podcast (28 November 2018) about fear, faith, hope and religion, US philosopher Martha Nussbaum makes an important case for the importance of the non-rational when considering how institutions might structure the political and its boundaries, especially when considering forms of rationalisation such as policy.

Discussing the question of faith in the future in situations where the widespread practicing of religion has become absent, particularly in Europe, the host David Runciman points out a view “from inside universities, particularly elite universities, [in which] there’s this view that the solution to these problems is better policy, there are kinds of intellectual, rational ways that human beings can get a grip over their fate again.” For Runciman this points to an inability for rationalised forms of future planning to create the space for faith in that future: “there is something about I think the overtly policy oriented or maybe rationalistic approach which misses that and is actually deeply alienating.” Here policy is taken as the rationalisation of the political — including things like fear; an attempt to define the boundaries of what constitutes acceptable fears and non-rational fears.

For Nussbaum, it is religion’s role in providing a structure to fate in the form of the hope, and the material conditions to change it in the hear and now, shifts what might be seen as faith in the non-rational to the infrastructure of what is considered a liveable life — where the imaginary is central to the materialisation of the conditions of life.

“I do think for many people who are isolated in society that’s the natural kind of group for them to turn to, and certainly in American society where people are so geographically isolated, where they don’t have other sources of social contact, particularly people who are aging, that is a particularly useful kind of group for them to form. I’m a member of a Jewish synagogue and I feel it’s a synagogue that’s not particularly theistic. It’s actually, like most reform Jews, we’re united by a desire to forward political justice. We have the largest food garden that produces fresh produce for the poor and so on. But, you know, being part of a group that’s doing those things is a lot better in many ways than trying to do them on your own. I also of course have a group of colleagues in the university and students, so I’m lucky in that respect. But I notice that people do get nourishment out of being a part of our group…

I’m a convert [to Judaism] so I know about Christianity but I was never asked, ‘What do you have faith in?’ You asked what you’re going to do. And you just don’t bother sitting around having faith, you get to work. And so that’s my approach. But I guess it is true that my great hero King did talk about faith as well as hope because he needed to address the despair and isolation that people often have. … Now of course King didn’t ask people to hope for salvation in the other world. Absolutely not. So he’s with me and saying what we’ve got to do is work in the here and now.… if you go back and you look at the end of the “I Have A Dream” speech you see that what he asked people to have faith in was not something that was other-worldly or even utopian. It was something in the here and now…. I have a dream that one day right there in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words interposition and nullification, one day, right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

This is useful for the question of infrastructure in a number of ways. Firstly, when Nussbaum speaks of the importance of at least a consideration of the role religion plays in not only defining the boundaries of the political for many communities, but also in how it helps stitch them together spatially and temporally. That is in and around other institutions or infrastructures of culture and governance. This immediately begs the question of the infrastructural role activities such as religion play in society beyond the institution of moral codes, ritualised practices and certain kinds of subjectification.

We can go further with this lens to explore how contemporary art might function as an infrastructure. The questions is whether it is as a rationalising or non-rationalising infrastructure. Drawing on Suhail Malik’s work on contemporary art as genre of approaches which include indeterminacy as a unifying style (see talk “Exit not escape – On The Necessity of Art’s Exit from Contemporary Art“), we can perhaps begin to describe contemporary art as a rationalising infrastructure: in that it creates the conditions for the standardisation, interoperability and portability of any critical artistic gesture within itself. That is to say, pulling back to the curatorial-institutional perspective of a post-Globalisation geo-politics of contemporary art, we can propose contemporary art as genre as a stylistic infrastructure in which to produce and contain artistic outputs within the specific infrastructural expanse of the art world.

The portability of contemporary art within its own and other infrastructures also relies on the ability for infrastructures to be layered, fragmentary, and though aspiring to totality, to be limited to their operating parameters and still happily function. This of course raises the possibility and indeed actuality of slotting one infrastructure (or the institutions and institutional instances it stacks together) into another: i.e. artistic or cultural infrastructure into the broader economic infrastructure.

(Here we can compare and perhaps align the approaches of the UK’s National Infrastructure Commission, tasked by HM Treasury with strategic planning of infrastructure spending and economies, and the Making Cultural Infrastructure report by Theatrum Mundi, which seeks to outline what the necessary conditions for artistic and cultural spending actually are; or simply consider the model of infrastructural import and connection offered by the international biennial or EU City of Culture model. The legacy of these time-specific events is clearly a pertinent question, and perhaps helps to frame the shift to thinking about infrastructure rather than globalisation. https://www.cultureliverpool.co.uk/liverpool-2018-legacies-of-the-european-capital-of-culture-10-years-on/; https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/impacts08/pdf/pdf/Creating_an_Impact_-_web.pdf; http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/513985/IPOL-CULT_ET(2013)513985_EN.pdf;)

In this scenario, one could argue that contemporary art looses its broad cultural relevance beyond very specific parameters — i.e. as entertainment, within specific institutional frameworks; as ‘critical,’ again within specific institutional frameworks; as value object, likewise within specific institutional frameworks; as a career or personal investment, within specific institutional frameworks — exactly because it evacuates its potential as a non-rational infrastructure. Once, aesthetics or religion might have taken up this non-rationalised space; today it might be various forms of otherness — which however is treated as a sort of object in the rationality of institutional representation or indexing. Certainly this rationalisation opens up a gap, or dead end where critique (something with its own frame of belief) reaches a limit — as it can be neither functional nor symbolic enough for the rationalised, standardised, interoperable infrastructure of contemporary art as genre.

However, contemporary art cannot properly accommodate the non-rationalised either until what is yet to be rationalised is rendered as contemporary art; or the art institution is critiqued and re-instituted (see Boltanksi); or at all — thus the difficulty or lag in change. Ironically the intersection of institutional faith and faith in redeeming it — as seen in the attempts to close / visualise the bridge / gap between stated and actual aims — might actually be the non-rational imaginary of contemporary art itself.

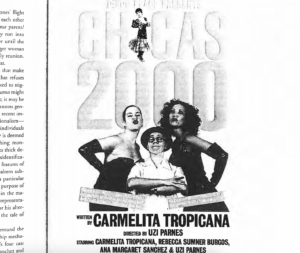

(Poster for Chicas 2000, written by Carmelita Tropicana, directed by Uzi Parnes; in “Latina Performance and Queer Worldmaking; or, Chusmería at the End of the Twentieth Century)

From the perspective of how contemporary art might then be able to be a non-rationalised infrastructure we might begin by looking to a shift in temporality. Moving from an “enactment of a desire for power in and over the real,” (Marina Vishmidt, in Sheikh and Hlavajova (eds.) Former West, 2017, 267) to a reparative expansion of what constituted “the contemporary” in contemporaries past, as described by Catherine Grant (“A Time of Ones Own,” 2016, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcw025); or the coterminous time made possible by the acts and structures of dis-identification proposed by José Esteban Muñoz in “Latina Performance and Queer Worldmaking; or, Chusmeria at the End of the Twentieth Century’” (https://doubleoperative.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/munoz-jose-esteban_latina-performance-and-queer-worldmaking-or-chusmeria-at-the-end-of-the-twentieth-century.pdf).

Here, a calculable or at least indexible relationship to the present as acquired through the infrastructures of contemporary art (including the market, academic and arts press discourse, and increasingly its integration into the timelines of social media), is disrupted as a strictly causal and dependable relationship. This is not to say that what Grant or Munoz suggest is irrational, just that this version of thinking through the infrastructural dimensions of art does not exclude the possibility of the non-rationalized from how it proceeds to make its worlds.

As I edit this I am thinking back to the final scene of Turner Prize winner Chralotte Prodger’s film BRIDGIT (2016) in which a rectilinear grid is overlaid onto a shot of a neolithic stone circle. The grid expands sideways, seemingly in attempt to encapsulate the shifting networks of relations and circumstance the stones coordinate. Its columns rush past the edges of the screen into meaninglessness, and a dog runs past the stone, its lead trailing behind it.