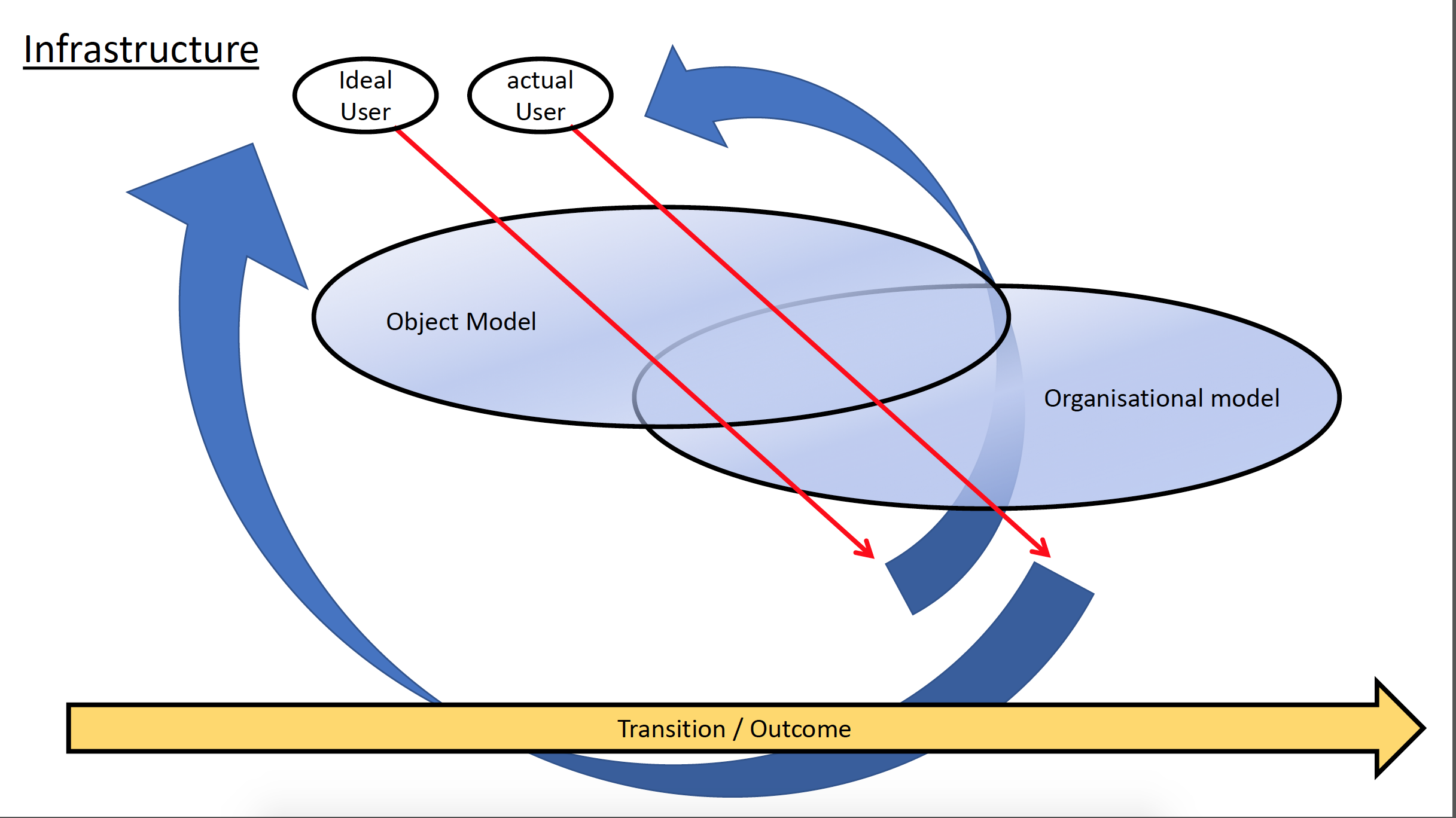

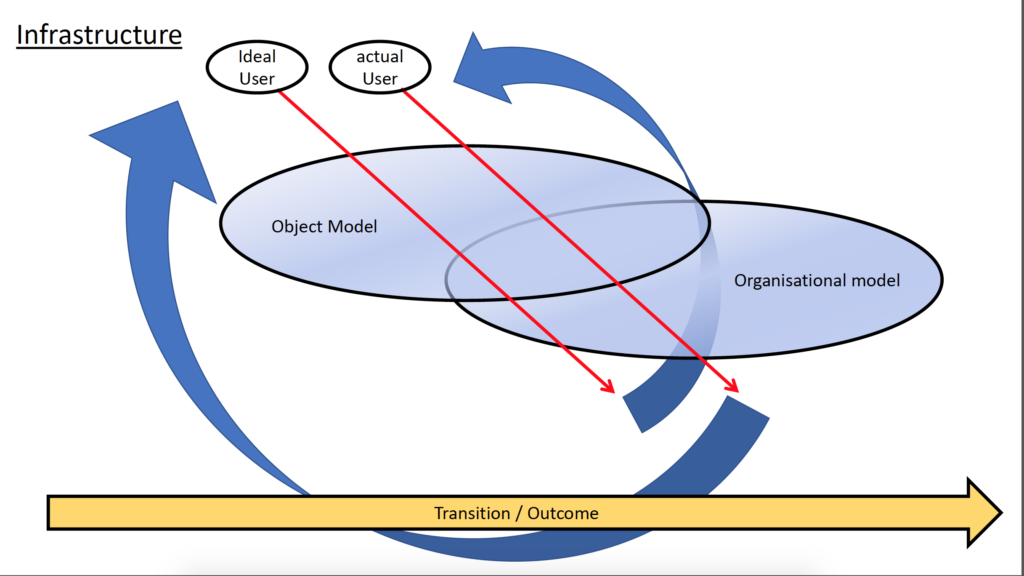

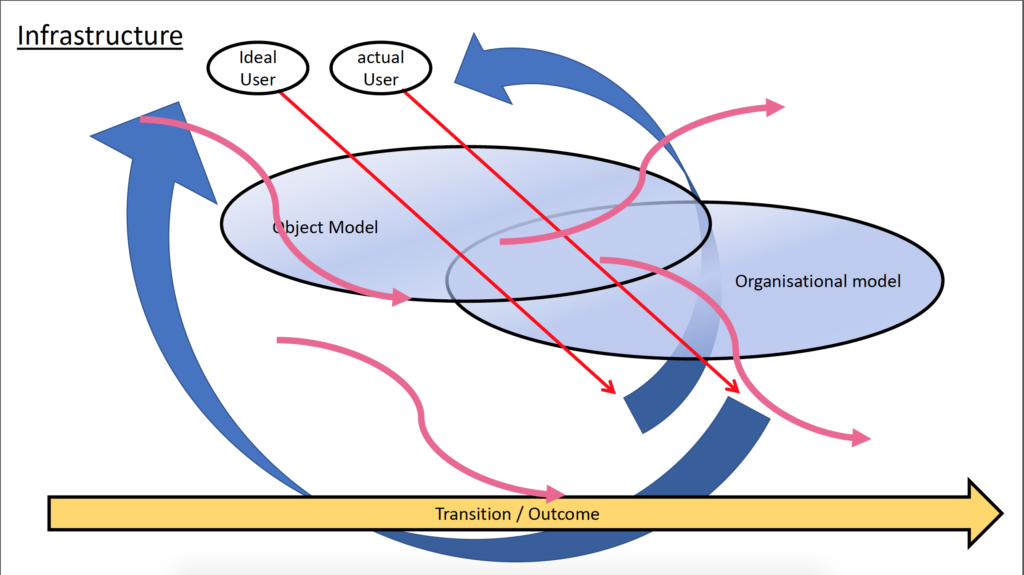

In this working diagram I attempt to explore how we might model (at a level of great of abstraction) the performative practicing of infrastructure. (It is developed in chapter 2.) This model is a departure from approaches to infrastructure that look to represent or describe anthropological effects, material/media conditions and consturctions for infrastructure, or to assemblages to abstract and describe infrastructure in ways that tie manifestation of infrastructure to specific conditions at the cost of a general model; looking to practice as a means of jointing these fields and opening up the knotty question of what it means to invent infrastructure (See also Easterling, Bratton, Munoz, Harun Morrison, What can a garden be, New Art Ecologies)

Where infrastructure is an assemblage in form, organisation and operation, so too must the diagramming of how infrastructure is conjured according to expectations about its availability, operation, reliable form, and to whom it is addressable. What is pictured above is an attempt at describing how various parts of infrastructure come together — in myriad ways — to keep infrastructure held together, often against dynamics within or caused by each part. Roughly, it is the performative and temporally, spatially and informationally circular relationship created between the imagined outcome, organisation and transition across the uncertain scale of an infrastructure and the manifestation of each of these factors with that imaginary holding in place that is the basis for infrastructure bing able to exist: since it is circular, where the conditions of existing must continue for certain forms of relational, contextual, information, technological and ecological existence to persist, it is the basis of a repetition that can be either (and most often) standardising, normative and tending towards transition or convention, or (more tricky, and for instance the subject of power relations, such as in ‘disruption’) the basis for invention and difference in repetition. This latter part is explore further below.

Diagramming infrastructure in this way develops the work of Lauren Berlant (2016; 2001) on infrastructure as pattern and on the circulation of form in order that it become genre, where anticipation and expectation require training before being naturalised as ground. It also pulls on the work of Thrift (2004) who joints the work of Berlant (2001) and Butler (Gender Trouble) to suggest a specific kind of performativity is registered in the particularly relational patterns of infrastructure, as relating to a technological unconsciousness. For Thrift, this technological unconsciousness can be through of as a circular cicurlation of form and expectation, carried out through for instance a sense of addressing and addressability that connects the parts of an infrastructure in how it is used and thought. To transit across an infrastructure we must have an address that we aim for, this address must be knowable to a user, and to the system; hence, to be infrastructural (a system or a user) requires addressability, internally and externally.

This relationship is represented in the diagram by the cicualtiey between ideal and actual users (but which could also represent use, outcome, process etc.,) as they pass through the organisational and object model (which come together as certain patterns). This addressability can, however, also constrain what is possible in the technological unconsciousness through, for instance, standardisation aimed at making addressing more efficient and predictable. As such, the circular relationship between expecting and enacting infrastructure is performative insofar as this movement through that patterning is both anticipatory and enacts what is anticipated: other wise the organisational work of infrastructure (Geoffry in Carse), would collapse. The provisional unity of infrastructure (Berlant) would not hold and infrastructure would cease to offer a transition across the meso-scale, spatially, temporally, or informationally. It would in Star’s terms be fully contradictory with its intentions, rather than simply invested with desire, master narrative and embedded practices that seems to contradict the hopes of infrastructural designers, and therefore through which this performativity takes place (1999).

It is this performative, or at least circular relationship that enacts infrastructure that is often most difficult to describe in the conventional models in the humanities and arts, since by relying on cause and effect, instrumentality, relationality, assemblage and pattern, it precludes the kinds of agency on which analytical concepts of invention and critique are built. Nonetheless, by grounding the relational modelling of infrastructure — often diagrammed in Deleuzean assemblage, or measured in cognitive science (Hayles, 2017) — in the specificity of form, event, or image as offered in the arts and humanities, we can begin to pin point this relational model (as for instance pattern), to differentiate it, and to invent it.

Finally then, the user, or the movement through pattern offers a variable which animates, traces, and potentially disrupts the patterning of infrastructure. Wright (2013), Bratton (2015), Rossiter (2017) and Chun (2011) have focused on the user as a point at which the rules (or repeating conditions and contexts) that hold together an infrastructure, suggesting this is both a submissive and potentially disruptive figure. On the one hand the as Rossiter and Chun describe, the user is required to submit to the expectations and rhythms of infrastructure into access it, thereby shaping their experience of reality. On the other however, as Bratton and Wright hint, this places a lot of emphasis on actors who are constituted but these infrastructures (meaningless without it) and who constitute these infrastructures; as such there is scope for Bratton and Wright to mis use and remodel this use — if we are willing to engage in the relational, instrumental terms of infrastructure seriously and comittedly.

Brought together, these factors raise questions on infrastructural agency and forms of disruption, how we might differentiate . Seen in Condorelli, Tsing is a need to contrast outcome, intention, form, shape, normativity. For Condorelli, the normally invisible conceptual, physical and labour infrastructures that scaffold the visibility of art offer an opportunity to highlight and rethink the relationship between the supporter and supported through notions of limited duration, supplementary, being brought up against or into proximity with others (2009). While for Condorelli this is relationality is built on top of an ethical framework built around the dynamics of authorship and participation baked into art critique, and as such is ultimately built around representational model of ethics, Tsing offers a relational comparison between scalability and nonscalability (2012). Built around standardisation of business expansion that allows the unchanging scaling up of a project or activity, regardless of the consequences for the contexts, ecologies, or conditions that scaling up affects, scalability is for Tsing, to be contrasted with forms of nonscalability activity which resist, inhibit, enable and complicate scalability. The difficulty for this model is how to make infrastructure where repetition and transitional scales do not rely on standardisation; how to make difference the internal driver and support of infrastructure. However, by, bringing together this dynamic practicing of infrastructure also here suggests it is the dynamic, meso-transitional combination of these two ideas.

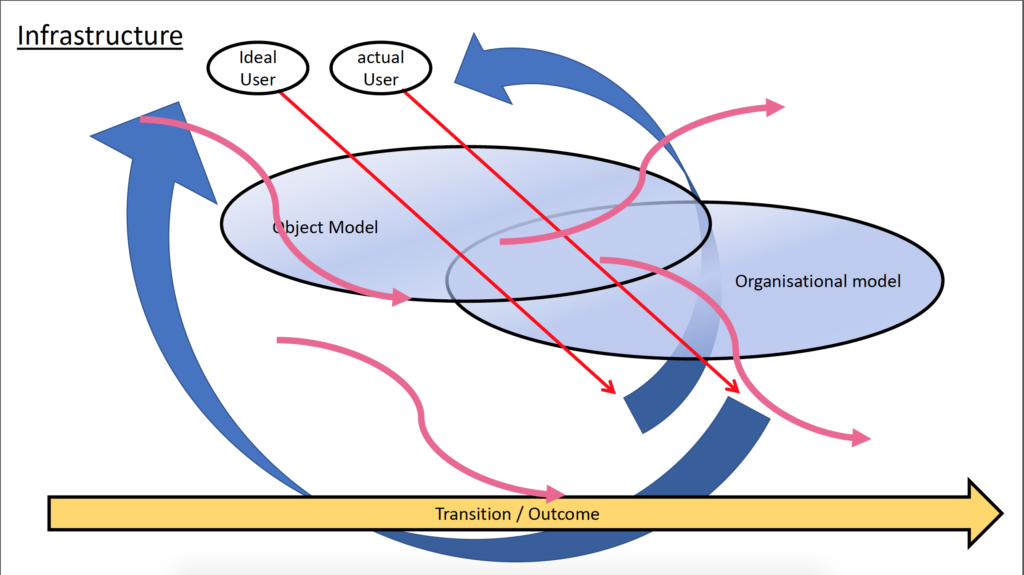

This leads to a second set of diagrams, where these relationship and movements are more scattered, less repetitive — whether by arrangement of parts, or by bringing into tension, one assemblage (or stack) with another, or by staging other kinds of meaning (imaginary) into these assemblages, or where movement through is itself patterned, imagined or conditioned differently — in order that difference immanent to infrastructure can be both given form and differentiated.

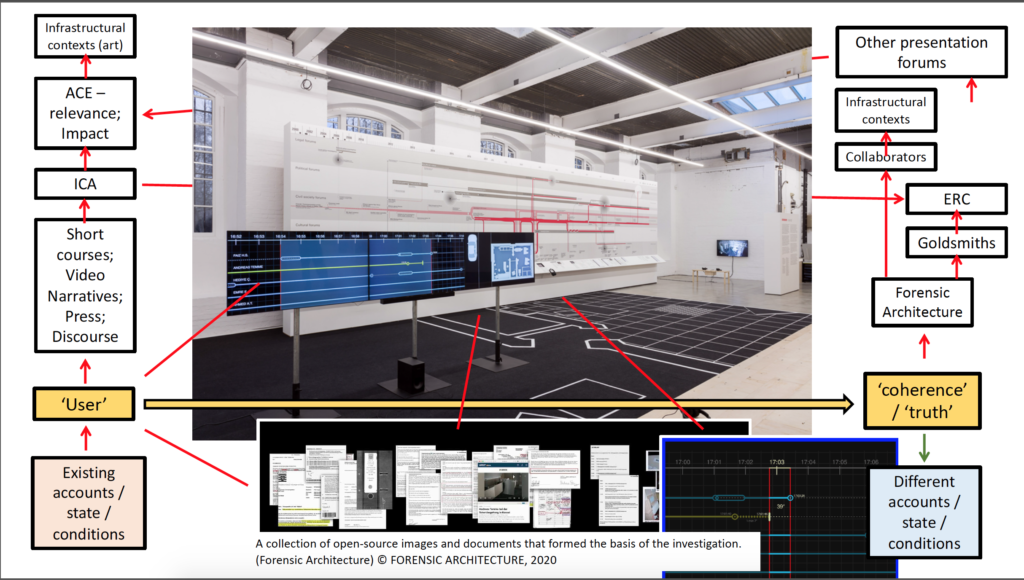

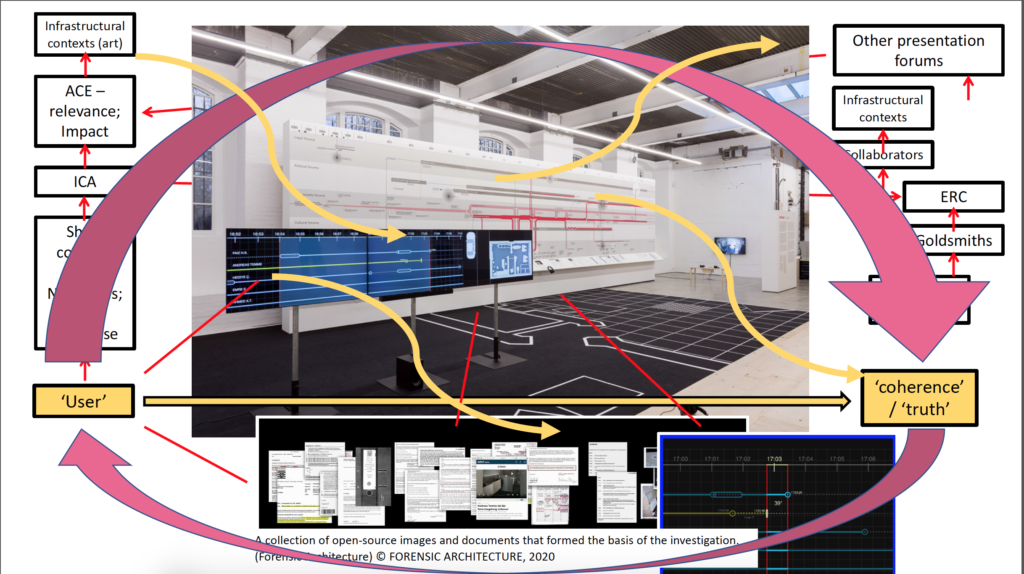

How would this look in practice? A key example I have explored is the work of Forensic Architecture and its staging in exhibition formats.

Where exhibition is our frame of reference, the proposal by FA represents a relatively self-contained and reductive model of possibility: a series of reports, timelines, videos and diagrams present a representation of an assertion or claim of truth, based on data extracted and assembled using architectural models.

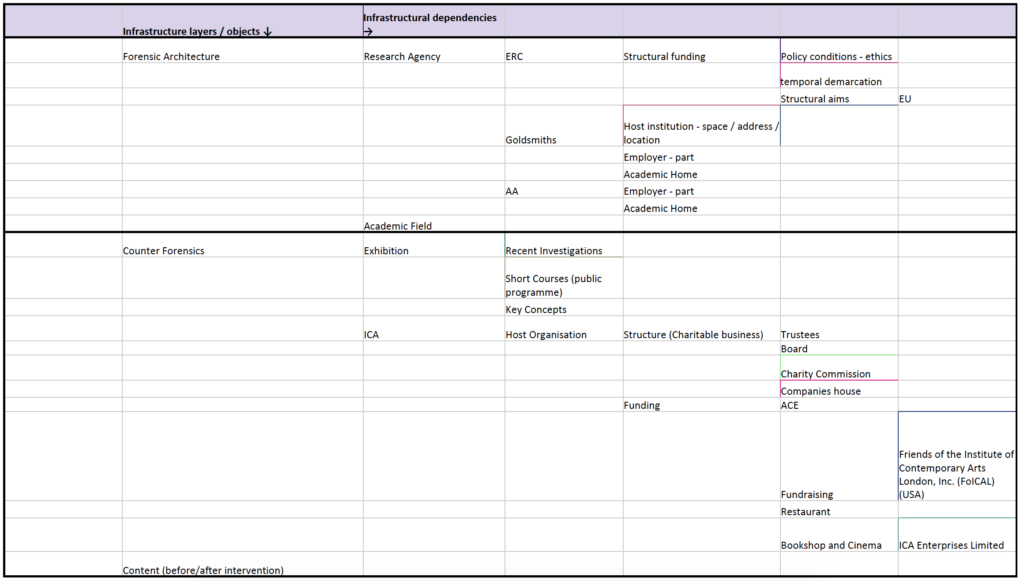

However, where we view this assemblage as an intervention whose scale and scope extends both beyond the art stack and intervenes in / interoperates with other infrastructures and stacks then the lines of transition and meso-scalar meaning are vastly more complex, and inter/intra-penetrate with multiple other modes / levels of meaning, staging, and practicing. (simply if we take an intersectional viewer of those coming into contact with it seriously this is the case.) We can begin to see this interrelationship with even a simply diagram of some footed infrastructural inter- / intra-dependencies of the work.

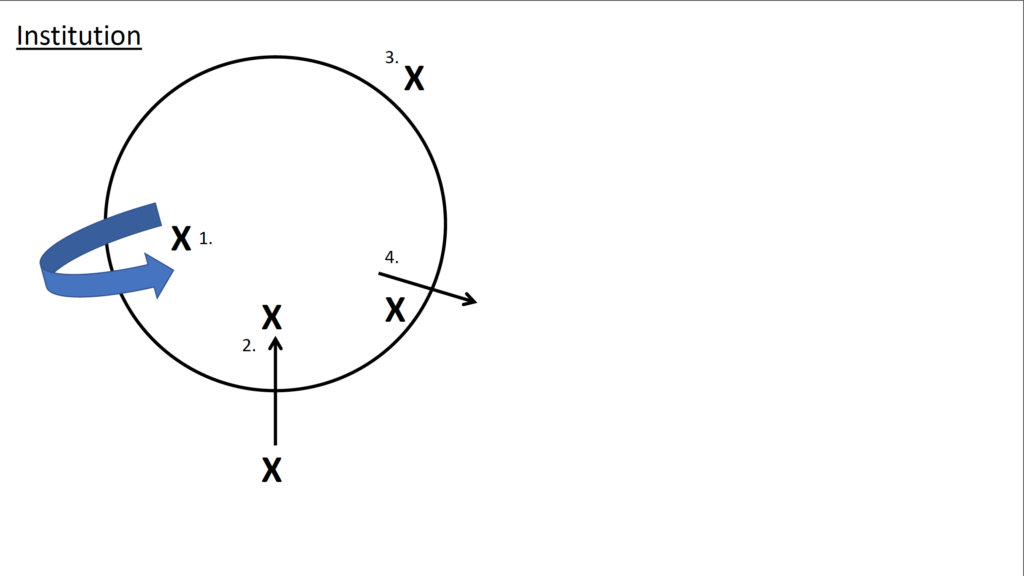

The question developed in the third chapter is specifically what this difference between representational and relational modes of staging and meaning are, and how, within a framework for infrastructural meaning, critical changes can be made. This will for instance mean the repetition rather than just inclusion of difference as a motivation of change; it will also mean thinking other modes of challenge and visibility to the infrastructural to those used in the critique of institutions: diagrammed below.

Classically, institutional critique can be summed up by 1. adjusting the meaning of the institution, where actors already inside seek to remake it via incorporation of an outside; 2. expressing the rub of incorporation into the institution for an actor who was outside; 3. by what or whom it excludes (these latter two are deeply informed by Foucault’s Knowledge and Power); 4. by escaping the institution. This forth approach, which generates it energy from the previous three, is often tied to either a life without institution, or by re-imagining it.

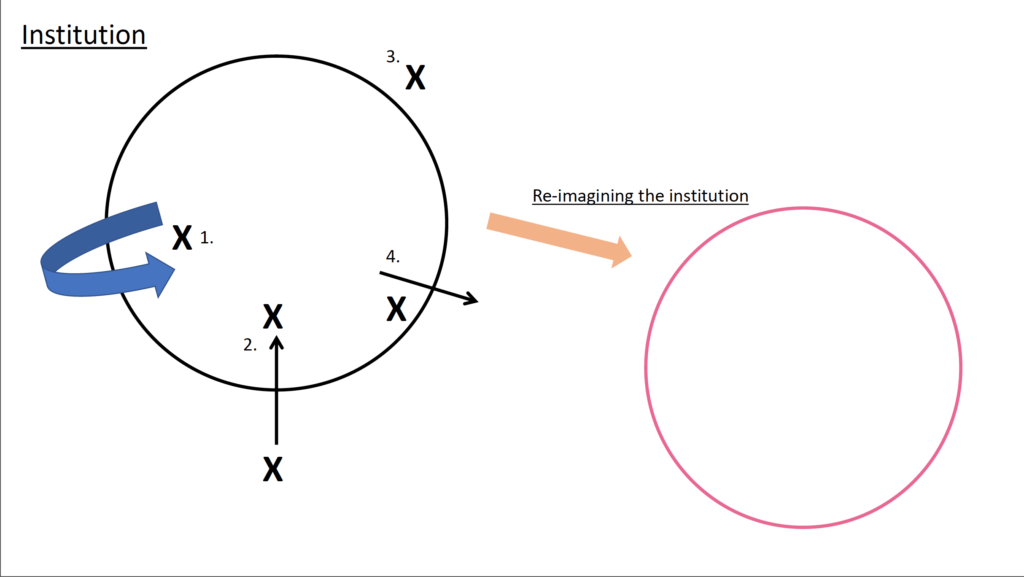

It is this final movement, of fleeing the institution to live without formalised institution, or to self-institute that I am principally interested in contrasting to an approach to complexification, change, re-making, patterning. etc., of the ‘movement’ or ‘transition’ through the meso-scale of infrastructure as represented by the pink arrows below:

The difference established for infrastructure will therefore depend on the development of an approach to thinking infrastructure as a practice that is more easily diagrammed as above, than described.