This is the first post written while on Residency at Rupert in Lithuania, June 2024. Hopefully, this can be a space for the thinking that happens, but which is outside of the specific things I want to try and get done / written. They can be read as thoughts in formation or as notes towards later texts.

—

Perhaps to my own shame, I hadn’t known how funny Donna Harraway is. Last night, I went to a screening of Fabrizio Terranova’s 2016 film-length interview, DONNA HARAWAY: STORY TELLING FOR EARTHLY SURVIVAL at Alt Labs / Sodas 2123 in Vilnius, Lithuania. The film began with Harraway describing at once absurd and mesmerising links and entanglements which, though of a piece with her wider conceptual frameworks of kinship and entanglement, also devolved into the hysterics, the excitement and potential of it all. Of escaping the confines of human-centred epistemologies, ontologies or organisational story. And with this, more specifically, this is those which delimit and confine certain ‘kinds’ or appearances of human as apart from and better than so-called nature, matter, etc. It was a warmth I hadn’t expected — perhaps foolishly given the rigorously freewheeling nature of her written work — but which created and enacted the conditions for one of Harraway’s central contributions: kinship. I was on board. (The film was made with a friend, a relationship Harraway later cites as being centrally important to her development / thinking / commitments.)

This warmth also leads a path to the other key themes of the film and Harrway’s work: story telling. Recounting another origin story, Harraway describes a family background and upbringing steeped in story telling and Catholicism. Again, a story steeped in laughter, Harraway talks about the importance and depth of storytelling that is foundational to her upbringing, sitting around the dinner table with her biological family each competing of the best story. Her father, she notes, was sports journalist for The Denver Post. He was not swayed by the glamour or prestige attached to ‘more serious’ topics like crime or business reporting, but wanted to tell ‘the story of the game’. I liked this a lot. That ‘everyday’, collective practices or intensities, or rituals of sport could be the source of so much detail, interest, difference and drama that it would be worth telling and recalling. That one could dedicate a life to its telling, to communicating that intensity, locality and communal narrative. It also helped to ground some of what Harraway would later discuss about the importance of a practice of positively making new things; of telling the specific knots, differences, attachments of this story, of the specific as the site where the general became unstuck and where the specificity of an other wise — ‘it’ — might be found.

Then, with another bout of perhaps more nervous laughter, she also acknowledges the problems, the power dynamics, the exclusionary, destructive aspects of this story of fascist-adjacent American Catholicism as well as her sometimes messianic attempts to lead the local children on religious missions — using this productively, or at least generatively, to offer an important framing for the role of storytelling and the kinds of kinship that can and must be built. That of inheritance.

How and why do these things become relevant and come together?

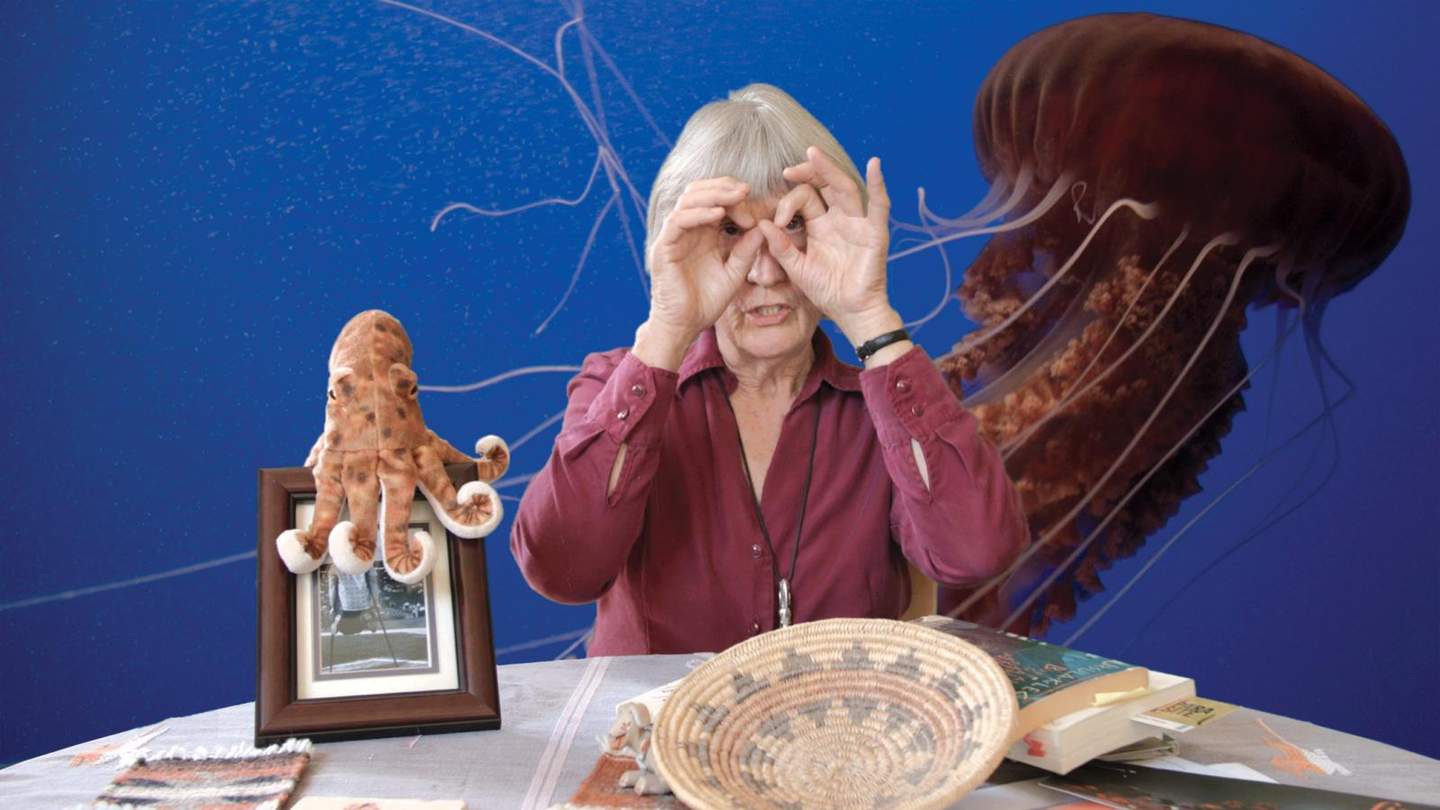

The artefact of film itself offers something of the texture and implications of Harraway’s work. Difficult to tell at first, but Harraway, who is talking to Terranova off camera, is filmed against a green screen and superimposed against footage of her house and office. The backdrop begins to pan disorientingly with Harraway appearing, doubled and at work in the background, or else with jellyfish floating behind or the room switching location at will or dropping out of shot. These parallel or simultaneous realities are heightened by archival footage of Harraway, her friends, or tongue in cheek TV lectures, or science fiction imagery collaged into the centre of the frame. Of course, you might say: these quasi-structuralist, post modern techniques of film making are of a piece with the digital era of hyper-situated, circulatory and disoriented story telling that often characterise contemporary visually-speculative narrative modes. (Indeed, the film’s director co-runs a masters in speculative and experimental story telling at Brussels’ ERG – School of Graphic Research.) Alongside this, through, the interview contained, for me, some key ideas and questions about what story telling might do in and to the world, and how.

Stories and kinship

I enter this having an interest in the ways that narrative can in the words of Meike Bal act as a motor or assembling device in a story (1999). For me, this can helpfully transposed to the repeating anticipatory narratives and practices of cause and effect that make up and hold together infrastructure; an infrastructure (and its transformation) is nothing without an animating story, purpose, outcome. That is, stories hold an infrastructural world up and keep it practically bound to itself (Rossiter 2017). Narrative can be an effective analytic and expository device when considering the often difficult to ascertain totality of infrastructure. It is especially used by environmental humanities and STS to convey the integration and significance of parts and constituents of active assemblages and the ways that they are situated and relevant (see Star 1999, Bowker 1994, Green (2020). It can also be a means of breaking and making other ways of being and doing together, at meso-scales since stories are one way that the anticipatory meaning and practices that allow infrastructure to be understood to show up as and where expected (Thrift 2004) become expected, relied upon (Berlant 2001). That is, narrative is one way in which the form that comprises infrastructure circulates to become a genre (Berlant), becomes habituated or relied upon (e.g., the ‘democratisation’ of information is how online platforms are woven deeply into everyday life becoming effective surveillance machines). The task, as is echoed/clarified by Harraway here, is to change the kinds of story that hold things together and what, and how and what can circulate so that how a world repeats or endures is different too. (On a damaged planet this is ever more important.) So what did Harraway say about stories?

To begin with, stories are key for Harraway to the possibility of other ways of being, for intensities to be felt, communicated, known and modelled; for them to become ritualised and to support collective being. She gives the instance of marriage, which though not at all suitable to the forms of kinship and family she lived and wanted, were all they had. They did a job, but were at the same time limited / limiting. This lead in Harraway’s story and work to a desire and commitment to find, tell, create other kinds of story; or redistribute the narrative (Harraway 1986). Towards the end of the film, Harraway narrates a sci-fi inflected story of another kind of kinship and biological entanglement: parenting is not limited to reproductive parents and at birth one is given a cross-species kin, or symbiont with which one will live and inhabit the world with. In this telling, the character lives in symbiosis with a monarch butterfly. While pronounced female at birth, the character decides she wants a beard. Because, in this story, the character lives with a symbiont, she chooses that this beard be of Monarch butterfly antennae rather than hair. A radically different story of what a family or kinship is, does and how it mediates relationships to the world, developing such shared, cross-species intensities are part of how Harraway instantiates the conditions of a wider project of imagining and exploring real and speculative non-extractive ways of doing and undoing. Of living on a damaged planet in ways that demand and enable other kinds of negotiation.

In contrast with this — or maybe towards this — she also discusses the dangers of stories becoming universal; of the power vested and invested in keep those stories universal or generally-applicable. Capitalism, capitalocene are discussed; their absurdity and violence is in their status as the only way of telling the story of human-earthly life — for those invested in it and those whose critique of it excludes any other way of thinking. (We need marxism/ists, but other ways of knowing too.) This occurs for critical terms too. Chulthocene, Anthropocene, are useful and limited, and in the case of the former a bit of a joke. They do the job, yet they risk becoming total, their difference becoming meaningless. The importance of this non-generallisablity is that it is allows for and is situated within the ways of being, doing, communing that are not repeated to the extent of becoming self-same, exclusionary, against alterity, entirely synthetic to a world of otherness. Rather, this specificity requires an ongoing negotiability; and a connected, recognition that in a dynamic, interconnected, and processual world of systemic and ecological interaction and niches, doing must also be about undoing. About living in the compost. (Here, to stay with the trouble is to stay with these edges: where the exclusion happens, but also the site where negotiation must — echoing Tsing’s concept of non-scalability.)

Ways of doing and undoing

So, while stories offer a conceptual frame for how ways of doing and being are known and held together, they also indicate or reveal the significance or consequence of the specificity those stories, particularly as they attach to objects or others and despite the tendency of some stories to become a generalisation. Why? The concept and actuality of inheritance, for instance, shows for Harraway the consequence of stories of and as ways of doing as they clash, negotiate, come into contact with others. Holding a Navaho woven basket she, as a white, American woman, inherits a brutal history of genocide on the indigenous American populations that means she must reflect on what it means to hold that basket in her hands. She inherits the story and impact of Catholicism in this place in this sense too. But turning to her dog, who is experiencing the onset of dementia and whose barks for comfort interrupt the filming, she also inherits a history of species companionship that allows her to comfort her dog, to make good on a relationship.

Between these specific instances, we find the tensions that can be set up in how stories and how we inherit them. That is, as ways of knowing and doing attach us destructively, generatively, abrasively, etc., into communities of others, and what might be called worldings — where such stories are generalised and enforced as the parameters and limits of shared or proximate existence. On the one hand, she holds and possesses an on object whose cosmology is dramatically at odds with the stories of conquest she inherits; on the other is a story of shared intensity of experiences whose inherited features (companionship, mutual training and responsiveness) cannot be fully known or defined and which generate ongoing mutual dependence. This tension is, then, posed in a non-reparative sense (Berlant, 2016), as a call to be attentive to and to tell and create moments or stories of specific attachment and entanglement. Not as representation in general, but as a part of a commitment to alternative ways of living. To living with the inheritance of a damaged planet which must be negotiated ongoingly as a reality and as a strategy of flourishing with it. This is a serious commitment.

Family-making and telling is, for instance, such a commitment. To be with, to support, to care for and to be cared for is a lifetime commitment and a serious one: especially when that family and kin are outside of the reproductive family, social norms, or species kinship, such as Harraway’s. It requires, rituals for those ways of being and of dying. This commitment to making and unmaking, telling and retelling, knowing and unknowing of rituals or ways of attachment and doing / undoing is both provided for and key to the metaphor and actuality of what Harraway calls living in the compost / staying with the trouble. That is, at once it negotiates and embroils us in the ways we must make as well as share and use the resources of a much wider ecosystem or assemblage of beings and needs; and that this pivoting towards both a wider net and a balance between giving and taking is the only way we can live, indeed maybe flourish, on a planet so damaged by extraction and capitalism.

These terms, of analysis and of a generative philosophy of a good life inspired by and out of this situation clarify and are clarified by the method or practices that it emerges from and what can be taken from it. Specifically, I am thinking of on the one hand the biography of Harraway and these ideas; she tells of building a house, garden and family whilst writing — and of writing only in the summer because teaching take the best of you. These activities, grounding and reflective, creative and iterative are key to understanding how other ways of doing and undoing might be realised. That is, through thinking and making; and making in order to give thinking life in its having to negotiate the assemblage it becomes a part of and which one must make ideas into. And on the other, a more generally-applicable lesson for the relationship of theory / practice proposed and articulated here together; we need a direction of travel / analysis & iteration that instantiates critical positions / propositions, and a positive, creative act which activate and which mediate / modulate the possibilities that theory / ideas imagine. What might be reality is made out of concrete contact with what already is. This changes what has been, and is the only way that something else might be. The last words to Harraway:

And yet the only the way to come into grips, to come into presence of it, … is to constantly keep doing positive things; you have to keep trying to make an experiment work. You have to keep writing this particular story, not some story in general, but this story. You have to do this. Be here, not everywhere. You have to be attached to some things, not everything. The only possible way is if again and again and again if we engage each other in doing something [laughs].

Watch:

Donna Haraway : Story Telling for Earthly Survival / Trailer / Fabrizio Terranova / 2016 from Atelier Graphoui on Vimeo.

Thus, this story is of how to create difference; to get to groups with it — that is, what is not the abstraction, but what is real, the trouble, the compost — the possibility of living outside the generalisation. The uncertainty of not being able to give or allocate a name to something offers the possibility of new meaning or practice. This requires the thinking of at least two temporalities or trajectories: the reflective and compositional and the grounded and mattered; or, to adapt Cornelius Castoriadis (as I did in my PhD), to imagine and institute, with the productive tension between them the stakes and what is at stake. Between these dimensions of story telling — narrative and the telling; repetition and inheritance — is where the negotiation and being with happens, that is, the ongoing negotiated co-existence necessary to living and flourishing with others. Important now more than ever.

For me, some open questions remain as to how this fares when in contact with structures for shared, common existence, however.

Infrastructural imaginaries (to redistribute the narrative)

A main question is one reflecting on the particularity of infrastructure, as that which must be known — or narrated — in advance if it is to be recognised as coherently infrastructural. Admittedly, Harraway is not discussing infrastructure here; however, the centrality of narrative to infrastructure, and of ways of doing and undoing Harraway discusses to how we might think about infrastructure means I can ask this question of the relevance of these ideas of story as they attach to, interface with, negotiate the category of things and practices that are infrastructural and, indeed, which must be also changed if the bigger project Harraway poses of living well is to be realised.

Specifically, this is the question of how to realise and sustain the conditions for these other kinds of life in dimensions outside of the personal or individual, familial or domestic (in its baggiest sense). This is not a difference in kind per se ‚— i.e., stories and inheritance play similar roles to those of anticipation and expectation of infrastructure — though the difference in scale, temporality, composition or location in infrastructures emphasise the question of distributing agency outside of the human story teller (which is nonetheless central to Harraway’s story here) more acute. That is, to reflect on the structuring dimensions of inheritance as the means of sharing that way of doing and undoing. And to be yet more specific, I am referring to how narrative or story-telling might, in a creative, positive sense might interact critically with the temporality of the loop of infrastructure. Both looping in advance of its realisation and as its reality (see PhD). In many ways, this is academic. Story telling enacts its own infrastructures of possibility through the device of narrative (Bal). But how this relates to or relays with both the practices and epistemologies this enables (Harraway) and the systemic arrangements, work (Carse / Bowker) and how these negotiations are ongoigingly negotiable/negotiated (Carse / Verran) and Configurable (Suchman) remains key to the durablity of these propositions as liveable and sustainable in a planetary sense.

The setting of creation and instituting

Another question is of the locus or agent of story telling and doing in Harraway’s work — at least as articulated in this film. (More work is to be done on checking this, of course.) For instance, the stories told here are ones of individuals interacting and deciding on how to live. For instance, choosing to model ones own body with Monarch antennae; the playfulness in kin making through symbiont from birth. The units are small and so there is a tension with the larger scales of relationship / relation that is some how un-addressed. Perhaps intentionally; but not sufficiently for my project. Here, then, I depart from Harraway’s approach, which like a lot of North American (post-Western) theory departs with an idea that individuals make themselves into a world, rather than a European one which imagines itself into or out of an already extant (and in many cases a priori / fundamental worlding, ontology, epistemology, etc., e.g., language, humanist, rationalist, etc.

Instead, I depart with the notion or inheritance of infrastructure, or infrastructure-like ways of negotiating being and doing in common as the meso-scalar unit or site for how we create into, know/sense and account for the shared, collective experiences of being in an environment with others. Of course, one could imagine radically non-human ways of being. However, in the same way that non-human organisms and matter creates structures or systems of existence and persistence, infrastructure is what we refer to when we refer to those initiated by humans. (I also blur this definition with institutions, which, like patterns in cognition are where certain kinds of meaning are stabilised, anticipated and recognised.) Infrastructure is thus, like the house or theory or family Harrawyay built(ds), a locus of thinking, support structure and interface with others /other beings / negotiation. As noted above, to centre infrastructure requires that we think about narrative in particular ways. This does not contest Harraway’s ideas discussed here, however. Rather, I think it offers a complimentary discussion of how we might address ideas of scale, scope, sustainability, or stability of such stories / ways of doing, whilst being attentive to the closure / generalisation that is an inherent risk in infrastructure. That is how to infrastructure with the trouble; to compost, do and undo infrastructure and the stories that tell it / it tells; to unbuild it as Halberstam might argue.

Redistributing the narrative.

To be imagined by infrastructure / imagine infrastructure is a way then of framing another aspect of how and why to redistribute the narrative; the purpose and location of other kinds of story telling. Do we need to address those ways of being imagined by infrastructure: post-truth, more than human sensing, knowing and the artefacts of the Anthropocene? To some extent, to know and think about where we are remains importnat; but Harraway’s project also provokes or is centred by the more foundational problem of sustaining shared life, and doing this well. The question then might be, do these complexities or their analysis support that foundational problem? Do we need to know about these in order to undo or unbuild them? Perhaps in order to unmake the cultural conditions or socio-technical in which they are genre or at least plausible as such.

Why as these questions? Because to sustain new ways of doing and undoing requires new kinds of narrative, character, story to be not only told and retold, but to be anticipated, expected, repeated as a ground on which that doing and undoing can endure. A non-sovereign relationality or proxemics made possible (Berlant 2016) in the ways stories allow for other kinds of orientation (Ahmed) to be sensed, known in those ways of doing and undoing; one which allows for the decomposition of that inheritance.

Perhaps this is exactly the role of the curatorial, to enable, support, imagine, assemblage the cultural, socio-technical performativity or rituals that will make other kinds of land use, kinship imagined, imaginable and institutable; and, following this, durable, sustainable and yet transformable. (Here Castoriadis’ turn to ecology and autopoeisis is interesting.)

This text is longer than expected. But clarifies and helps to weave a number of threads that I have been considering. Specifically as to the point and articulation of a practice that crosses academic, curatorial and writing/creative practice; of the relationship between infrastructures to cultural / more than human settings, and the kinds of conceptual / performative devices through which these are known, sensed, repeated and inherited, such as narrative and configuration.

—

Thanks must be given to my host organisation as this research and time has been supported by Rupert.

x

12-6-2024